… it’s so real. The movement of the poem without breath evokes exactly the situation it describes

The wonderfully titled ‘A Parishioner Complains at a Parish Church Council When We Move the Time of Evensong’ by Manon Ceridwen James is the IS&T Pick of the Month for January 2022. Voters loved its wit and the fact that that humour was tinged with warmth. They saw poignancy within its acutely observed reality and ‘enjoyed the stream of consciousness style of prose‘ and the fast pace that threatened to overwhelm. But there was also a message there that things need to change and that change will not always be welcome.

Manon Ceridwen James is based in Wales and is an Anglican priest, feminist theologian and adult educator. Her poetry has appeared in several magazines and her book, Women, Identity and Religion in Wales, based on her PhD research, was published in 2018.

Manon has asked that her £20 ‘Prize’ be donated to Haven of Light CIC which takes action against Modern Slavery, Human Trafficking and Exploitation

A Parishioner Complains at a Parish Church Council When We Move the Time of Evensong

You have changed the Bible you have changed the words in the service you have brought in girls to serve at the altar and women can now be sidesmen and any minute now you will let that priestess next door with her earrings and clacky heels come and take the service when you’re on holiday and anyone can now read the lessons but I liked it better when it was just me and the headmaster and we now pray for all people instead of all men and you have changed the creed to say that it was for us and our salvation that Jesus came and not for us men and you have changed the words of Onward Christian Soldiers where would you be without our soldiers we would be speaking in German and you want to charge a pound for coffee a pound this isn’t Starbucks we’ve always had coffee in the coffee morning for 50p and it was nicer when it was made with milk not water and now you are moving the time of evensong from six to six thirty this really really really takes the biscuit.

Other voters’ comments included:

The echos of a Church – going… going… gone (almost). A torrent of nostalgic rant climaxing with outrage over non milky coffee. Beautiful evocation of people and place.

It captures the spirit of complaint with an almost affectionate critical generosity – there is understanding amid the frustration. The shape and structure convey the experience effectively.

It enjoyably encapsulates a theme that I find interesting: the quest for spiritual balance and the frailty of humanity as the perpetuation of that quest. At the same time, the poet’s biography, plus the voice of the poem, gives a contrast of hope against this bleak theme, because she hasn’t given up. The form of the poem is well chosen and enables us to empathise with the person spilling the hypocritical rant as confused, and the victim of modern society. I find the poem perfectly balanced.

It’s very true to life and resonates with my own experience

People don’t like change but if we never changed imagine how difficult life would be for a woman [in] today’s world if we did not have a voice. We all need a voice and sometimes only change can help a voice get heard.

Funny, poignant and real

It resonates with my reality 😆

So acutely observed, and wittily done – a lovely light touch

I enjoy the humour this poem evokes, despite it being tragically true. The fast pace also evokes the feeling of being overwhelmed, just like many church leaders feel in the face of a barrage of grumbles. I feel panicked just reading it!

I agree with her beliefs, we must move on with the times, and we are all the same.

I rang my sister and read it to her the day I read it and then told people about it because I thought everyone should meet it!

So, so true!

This poem cleverly and simply represents the parallel tensions of macro change within the church with the micro world of the parish day to day. It also provokes thought to the trivial viewpoint towards women’s ordination. Thank-you Manon

Manon writes with such warmth and humour … capable of uniting us in our shared humanity 💞

Speaks volumes of the changes and ideologies of the modern Church in Wales.

Absolutely accurate but heartbreakingly funny at the same time

It brilliantly portrays the list of stuff that gets hurled at ministers!

Captures the mood and attitude of church council meetings perfectly.

I have lived through conversations just like that. I love that feeling of being stopped in my tracks by the authenticity of Manon’s poetic voice.

**********

THE REST OF THE JANUARY 2022 SHORTLIST

April again and wet by L Kiew

L Kiew is a Chinese-Malaysian based in London, and works as a charity sector leader and accountant. Her debut pamphlet The Unquiet was published by Offord Road Books (2019). She was a 2019/2020 London Library Emerging Writer.

•

Sister Death Sits on the Back of the Settee by Hannah Linden

It shouldn’t be such a surprise. She knew

me better than most people, after all.

So cosy. And yes, in the womb

I gobbled her up and thought I’d won.

But you forget such things.

Behind me like a pantomime catch-phrase –

never where I’m facing. Sometimes

when I’m watching TV, a slight shadow.

Memory plays tricks on you, like that.

It’s inevitable that the settee will sag

and she won’t be able to resist

patting me on the head

the way you would a child who thinks

they’re becoming your equal.

Is it too early to say she will be my best friend

one day? I offer her presents, let her know I love her

but she’s family, knows all my tricks.

She’s taken to leaning into my shoulders

moving with me when I try to dislodge her

with cushions. I don’t want her comfortable

but she fluffs them up with her fists

and puts them back into place

under her elbows.

It used to be a game. Now that she’s winning

it isn’t as much fun.

I know I’ll accept her one day, that the sag

in the settee will feel just right. But sisters

never make it easy for each other. I make

a sudden move so she slips awkwardly,

loses her balance.

I know she’ll forgive me one last side-step

whilst I nip out to the bathroom during a commercial

break, wash my hands of her as I slip out the door

on my way to a party. I don’t invite her.

Hannah Linden is published widely including or upcoming inAcumen, Acropolis, Atrium, Lighthouse, Magma, New Welsh Review, Prole, Proletarian Poetry, Stand, Under the Radar and the 84 Anthology. She is working towards her first collection. Twitter: @hannahl1n

*

Dressmaker at the market by Jackie Wills

I stop at the dressmaker’s stall

to ask what she does with leftovers.

We discuss bunting – it’s a slow day.

I buy a £10 bag of scraps, swatches,

snippets, interrupted patterns

and borders. The bag taps a morse

of promises against my leg – eyes

outlined in gold thread, dots, dashes,

all the birds of the world in repeated

murmurations and mating dances,

lines of ladders to the moon: promises

as they’re meant to be. They unravel noisily –

metres of cloth anticipating weddings,

funerals, birthdays. My bag of patches

and irregular lines makes do, invents a flag

of no particular country, resurrects a hand

from the place an arm was cut to conduct

more songs of love, redemption, surrender.

Jackie Wills is a poet, prose writer and editor. She has published six collections of poetry – the most recent is A Friable Earth (Arc, 2019.) More here: http://jackiewillspoetry.blogspot.com

*

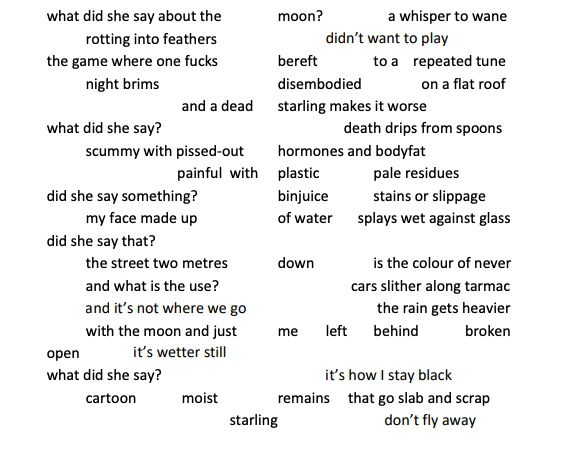

You can find the full text of the poem (including Marc’s concrete poetry images) here.

Poet and musician MarcWoodward has been widely published in journals and anthologies. His collections include A Fright of Jays(Maquette 2015), Hide Songs (Green Bottle 2018) and The Tin Lodes – co-written with Andy Brown (Indigo Dreams 2020). His new collection Shaking The Persimmon Tree has just been published by Sea Crow Press. Find him on his blog or on Facebook.

Andrew Woodward is an artist and film maker specializing in kinetic sculpture. He graduated in painting and video editing at Bath College of Art and has established a reputation with his kinetic sculpture / automata, and welded figurative sculptures. He has exhibited in London and across the South West, and his work is held in collections nationally and internationally.

•

Andrew McDonnell reviews ‘Fresh Out of The Sky’ by George Szirtes

Mary Borden, in her forward to her WW1 modernist memoir of prose poems, The Forbidden Zone, writes how her pieces are fragments of ‘a great confusion’. The poems that make up a great part of Szirtes new collection are themselves fragments of a great confusion that the 20th Century was so good at creating. For Szirtes in particular, it is the Hungarian uprising and his family’s flight to the UK, as echoed here metaphorically by both the title of the collection and by the artwork of Clarissa Upchurch of a plane coming into land. Of course, the poems here speak beyond their own historical moment to any family fleeing danger and seeking a new life. His experience has been repeating and repeating, day after day on the news and on the beaches of Europe and I found myself thinking of both Szirtes earlier poem ‘My Father Carries me Across a Field’, and our chief demagogue, Farage, pompously standing on the white cliffs of Dover blowing his dog whistle into the wind and getting hit with it in the back of the head.

What is the legacy of the 20th Century for Europe? This is a question that we are continually asking, attempting to feel our way around the horrors of the Nazis; the Cold War; the constant face of antisemitism and other forms of prejudice pushing their face over the garden wall of our culture; the upheaval of people, of families who find home amongst the ‘bleak terraces’ and watchful eyes of the neighbours who ‘can’t keep track of all their comings and goings’ (Meet the Neighbours). We rise to meet ourselves in these poems.

With each collection, the past is redrawn through a mastery of form that we come to expect from this poet, (Szirtes is surely our contemporary master of both the terza-rima and sonnet crown). These formal poems lead us to surprising imagery, where a youth puts out his cigarette ‘on a woman’s shapely thigh’, or the command to not be fearful of how trains in the UK ‘divide and where they go’. Trauma and history dance at the edges of these poems to Al Johnson; arguments through floorboards; phone calls and a ‘landlord’s dog’. It captures an England of coldness and indifference and the strangeness and the stranger. The adult remembering the child’s experience and trying to puzzle it out.

However, that great confusion doesn’t just belong to the 20th Century. This collection also points towards our own great confusion: our plague times, our weak world leaders and their gerrymandering, the tensions between nationalism and globalisation. It is a serious book and a book which deserves wider reading and discussion.

The collection is divided into five distinct segments. The second segment is a dialogue between the poet and his late father. This section haunted me for days and each re-reading offered new questions and ways of seeing. The success lies in its form, which works to create an oppositional writing that challenges the way in which identity is ascribed, both in the larger sense and in the personal. At times the poem works on metered stanzas before suddenly fracturing into lines that move across the white space like exhaled smoke or fog. The unnatural narrative of the poem (who exactly is speaking when the poem shows us that absolutes are the path to disaster?) resists and the resistance is powerful. In the first part, ‘Waking in the Yellow Room’, the speaker tells us to resist not just those who would seek to assign us, but to also resist self-assignation. In ‘Ring Circuit and Stalemate’, the middle section reads:

No point arguing with their dead, still less so

With yourself. All one makes of that is poetry,

Which is no consolation. We are at a standstill

You and I.

I see you playing cards

In a garden with your friends, a cigarette

In your mouth. You offer me a cigarette.

You show me a handful of foreign cards.

You explain the rules. You sit so very still

It is as though you were composing poetry

In your head but you will not say so.

The subtle shift in tense from present to past in the penultimate line adds to the dreamlike quality of the poem. Nothing is what it seems, and knowing is frustratingly beyond the son, and yet that frustration is a better state than those who sit in ‘The Yellow Room’ certain of their own self-definition. Through this unnatural dialogue, resistance is shaped in new and surprising ways. It is also deeply moving.

The collection accumulates more and more dreamlike power. The section Going Viral plays with the language of Covid and the war metaphors poorly employed by the government are nicely skewered here. The poems are infused with a deep scepticism for the language of emergency, the hyperbole of the Ministries, asking how we are supposed to find the space to live in the seas of anxiety while corruption openly happens before us. These poems also complement the earlier poems in their sense of history repeating:

Nobody had died

It was there in the records

That we had not died.

In recent years, who has not pinched themselves and asked, ‘am I dreaming?’ From Trump’s chaotic made-it-up-on-the-back-of-a-fag-packet administration to our own current incumbent mess of a PM, never has it felt like we are in a waking dream where truth is sold down the river to the highest bidder and then drowned.

In the fourth segment, we enter dream songs with quatrains and sonnets rushing forward through hypnogogic logic and riddles. The speaker of the poems finds themselves waking into nightmares where things have been stolen, trains are late, trouble is coming, ghosts walk town and tunnels, and the speaker wakes up dead to another version of themselves on tv ‘with a name I could not speak’. These poems circle us back through earlier sections, fracturing the logic further, taking us into surreal territories. They are compelling and rather than being a nod to Berryman’s dream songs, these remind me a lot of mid-century European poetry, from that of Holub, Holan etc, to the matter-of-fact surrealness of Francis Ponge (The CB Editions Ponge is worth consulting) and of course, Kafka. Szirtes has a knack for making his voice sound utterly calm and logical in this regard ‘Fake news said the light in my brain. / Trust me, it’s fake, it repeated’ (Dream of Moldova).

The collection ends on a different note with Bestiary, a playful series of poems that combine addictive doggerel with prose poems and bought to mind Borges’s Book of Imaginary Beasts and somewhat randomly Shel Silverstein who I often read to my kids at bedtime. My favourite here is the Stag Beetle:

Horned demon, stag beetle,

Half-insect, half Swiss-army-knife,

Your armour seems impregnable.

Have you come to take my life?

The shift in tone between the quatrain and the prose poem is what make this bestiary a pleasure to the ear. I recently finished Russell Hoban’s 1981 speculative novel Riddley Walker, and the quatrains here reminded me of the songs and poems the characters sing as didactic lessons about the world, creating their own mythology and wariness. There’s a real pleasure in these closing poems that left me wanting a full bestiary with sketches of the beasts.

*

I took some time away from the collection after writing the first part of this review to reflect on what I had read. One of the problems of writing a review about poetry is that poetry is not immediate, not instantly consumable (Actually, problem is the wrong word here – not being instantly consumable in the age of Instapoetry is welcome). Poetry needs time to work through to the core and the poetry of Szirtes is rewarding when you give it the space. The Yellow Room section of the book has stayed with me the most – I read out a section to my partner, about resisting being assigned identity by others but also oneself, and how that resonated in terms of a conversation we were having about class and intersectionality.

The world has irrevocably changed and the poems in this book speak to this contemporary moment. The poems recreate the dreamlike reality we find ourselves walking through. These poems are generous, personable but come with warnings. Szirtes is listening carefully to the world that is in a fugue state, walking randomly from disaster to disaster, often unable to link history to these moments, and beneath that fugue, we find ourselves, and the hope and promise in the circumstance that so many of us have heads.

Fresh Out of the Sky(2021) by George Szirtes is published by Bloodaxe Books and available here: www.bloodaxebooks.com