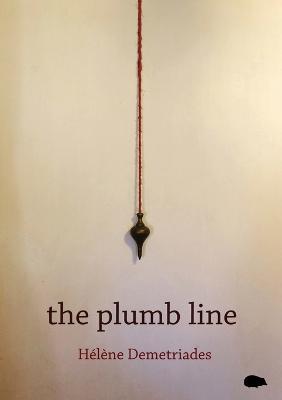

Hélène Demetriades’ debut collection, The Plumb Line, charts a life in three sections. The act

of ordering gives rise to measured reflection. Complicated experiences are held up to the light and

this considered examination perhaps allows certain chapters to then be closed. Démètriades is a

psychotherapist as well as a poet, and these works are clear-eyed and knowledgeable, written by

someone unafraid to turn over rocks and observe what squirms in the darkness.

Poems written in the first person aren’t necessarily about the poet—of course they’re not—however

these do follow the chronology of her life. It seems these poems are unashamedly intended to be

seen as expressions of personal experience—Démètriades makes no attempt to hide, and indeed uses

poetry as a way to give a voice to a child who was denied that right.

The first third of the collection is entitled BEGINNINGS and charts the poet’s childhood, starting

in Switzerland. ‘Let me slip past an old orchard,’ (IN MY WORLD)…

in a bright blue cardigan,

April unbuttoned, the quilt

of snow thrown off.

Unsettling images soon mar the idyllic landscape. The child sees, ‘a rat’s corpse on the wall…

maggots devouring it to bone tracery.’ There is a description of being in a childminder’s home

where kittens get drowned and the child is assaulted by a lodger in the attic.

An abrupt relocation appears with a poem entitled EAST PRESTON—the reader feels a sense of

being plucked from one place to the next. And now the child is thrown into a depressing landscape

where she stands:

On a pebble beach draining into grey sea

a place so desolate I feel my life has died.’

In this new home, each scene again contains an undercurrent of threat. In the garden is ‘the

raspberry cage where Daddy stones a blackbird.’ (WHITEGATES I) and the kitchen has ‘a

chequered floor / where I cower, small pawn, arm across my face.’

Throughout these poems, the father is a volatile, menacing figure, and the mother distant. The child

has no reported speech in these poems, except for one where she (perhaps a teenager now) says: ‘No,

I’m not doing that,’ to an adult who masturbates beside her in a car (APPEASEMENT).

I found myself starting each poem with a small twist of trepidation for what this silent little girl might

be about to encounter. They are unsettling due to the quietness with which these disclosures are

revealed, as if long held-in. The stunning Swiss scenery adds further incongruity. The quietness is

achieved through spareness—each image is precisely described, there’s little punctuation and good

use of white space provides pleasing variety of shape and form. The very artistry of having used

poetry as a means for exploring this complex subject has allowed the poet’s insight to grow through

the slow work of writing.

The poems move to a middle section, entitled GRAVITY, focused on the narrator’s parenting and

adult life. Here, experiences trigger memories, such as when the speaker’s grown daughter brings

back food from her job in a supermarket, reminding the narrator of her father bringing:

bags of dusky pistachios from Greece

Gruyère from La Suisse.

Every evening the kitchen was filled

with his bounty and tyranny.

(GOODIES)

Some of these poems seem more distanced, perhaps to protect those depicted. Nevertheless, they are

thought-provoking, deft sketches on moving forwards despite past trauma, on the joy and pain of

mother-daughter relationships and a child’s growing independence.

The third section returns to the narrator’s parents, now in old age. These make for a deeply

considered portrayal of what it is like to relate to a parent who did not treat one well. Indeed, not

only that but also what it is like to actively provide care for such a person. Poetry becomes a

powerful, artistic means for interrogating incredibly complicated emotions, presenting them with no

simplistic answers.

This is a collection that consoles by showing ways to look at pain and brokenness fearlessly and with

compassion. There is no easy resolution, but with breath-taking spareness the poet pinpoints searing

truths: in HAWK the father’s reduced state is described as having ‘clipped wings—his soul is

outraged.’ And then FIRST STEPS ends with what struck me as summing up the whole flaw of the

father:

On the phone the next day in different countries

you confess you hadn’t really seen me.

Zannah Kearns is a freelance writer and editor. Her poems have been published in The Dark

Horse, Poetry Birmingham Literary Journal, Finished Creatures, Under the Radar, South, and

elsewhere. She is part of the team who organise a monthly open-mic event in Reading, The Poets’

Café.

The Plumb Line, by Hélène Demetriades is published by Hedgethog Poetry Press, and can be

bought here.