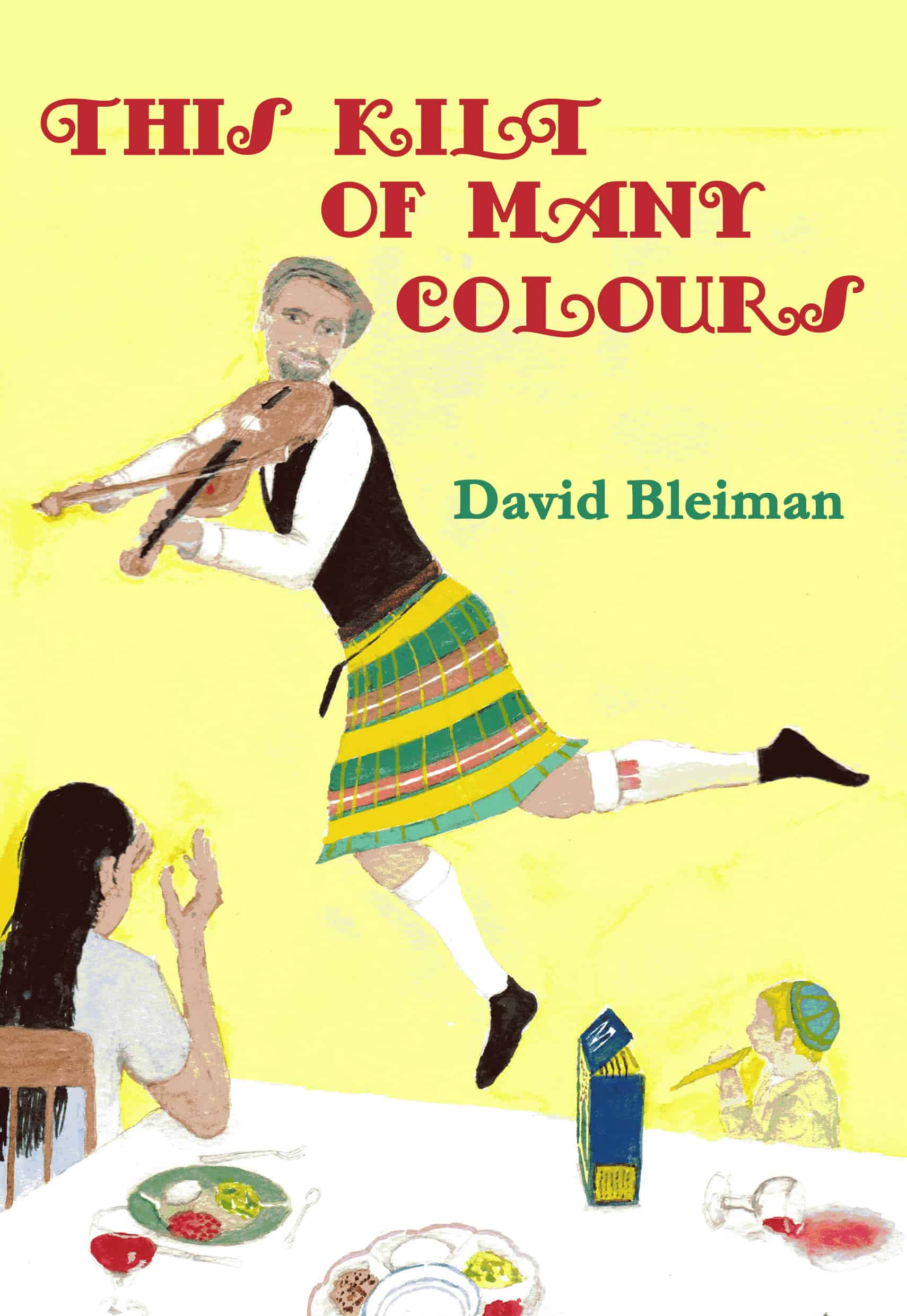

This Kilt of Many Colours by David Bleiman

Dempsey & Windle

ISBN: 9781913329457

This collection of 24 poems is a celebration of multiple identity. It’s also funny, moving, mocking, sad and slightly wild. Why the title? David Bleiman lives in Scotland but has a Jewish background with family connections to Russia and Eastern Europe, latterly South Africa and Spain. The kilt is a Scottish image but equally can have many colours, not just tartan. The poems are a counterblast against shoving people in boxes. They show why Teresa May was wrong: citizens of the world are also people from somewhere. We can choose to be both.

First is “Duende” a Spanish concept which signals an overture, a clearing of the throat, forceful and with feeling. It gathers memories of falling in a distant childhood playground but then defiantly rising to seize the reader. What follows are more memories and stories, drawing on Moscow, Fife, Granada, South Africa, weaving a cloth from family and beyond. “Lacquer Wood Fiddler” tells of a small wooden Klezmer fiddler, found in Russia, carved in a Jewish shtetl, mute witness to history.

Language is a playground, not a prison. Many of the poems are written in a riot of Scots and/or English, with a sprinkling of Yiddish or Spanish – all understandable (though there are welcome footnotes) which is wildly original and funny. “Why Dae A Scrieve in Scots?” is a tour of Spanish, Scots and Yiddish (macaronic) showing how – of course- any lively voice is mutable and multiple. “The Trebblers Tale” is a fabulous ballad of a Jewish trebbler (traveller, chapman) plying his wares in Fife, “weel-kent by mony a lanely wife” who has sadly long since gone and with it their unique blend of Scots Yiddish – recreated here. Burns might recognise Tam o’Shanter in the Jewish peddler.

This is broadly free verse but not wholly unstructured; most of the poems have a few stanzas of broadly equal length, using some rhyme and a loose sense of rhythm strongly based on conversational speech – they really should be read aloud. There is often a repeated emphasis, at the beginning of each line or stanza, with poet talking directly to the reader, (“you”) and much assonance and alliteration which gives his voice the musical sound of speech. Take for example, Shvelbele (little swallow), where the search for the lost letters, maps or memories of previous generations is compared with the migration of swallows:

Will you find what I have buried

there in reedbeds where I roosted,

resolving to return,

in some marshy mud nest,

down where brackish waters wash

or in eaves of outhouses,

lodged on ledges out of light?

Form varies; some of the poems are short ballads telling a story such as The Ballad of Fuente Grande or The Trebblers Tale, others a looser meditation such as Rowan which is a lovely prayer to a new grandaughter; many poems reference music both overtly and in rhythm and sound: Singing with Sasha in the sukkah. But what will most strike most readers (or listeners) is the extraordinary and highly unusual range of language: Yiddish, Scots, English, German, Spanish – all in a glorious mish mash, singing together.

Memory matters. “El impacto del olvido” (the impact of forgetting) mourns the 1492 expulsion of Jews from Granada, the pressure to forget and move on, which allowed history to repeat itself in 1943. “Place Markers” muses on original US names like Manahahtaan or Checagou, almost lost, along with Gharnata (Granada). “Auf Wiedersehen” softly shows the letters from lost Litvak cousins, postmarks stop in 1941; then changes gear and demands the right to reclaim German “not with a veteran’s iron cross/ but alone in the past where my records spin”.

Many of the poems are about family. “Dream mash lullaby” is a “squeeze of honey in cinnamon milk” with a lovely, rocking, soothing rhythm. “Peace be upon him” is a tribute to David Bleiman’s father alongside an acknowledgement of his father’s father’s stinginess; neither was an ideal; yet “refreshing memory with tears/I cannot say “my father”/ without his wish for peace.” The poems breathe warmth and humanity.

The political multiple identity message is never far. “Marmalade” is the title of one of the three group of poems. It includes “Bitter Fruit Ripening” which pictures king Carlos, who built a cathedral in the great mosque at Cordoba only to “recoil from the intrusion”, appalled. Centuries later “here at home, friend, a grasping gale/ tears our blue flag set with stars/ another boy who dreamed he would be king/ observes what he has done”.

Nationalists take note.

Tom Wilson ran Unionlearn, the education arm of the TUC. He has written widely on adult education, including for the Guardian and Independent. He is a founding member of the Lewes Book Club, the Lewes Literary Festival, and supporter of the Charleston Festival.