‘What’s real is us’

‘Can any amount of words stop a thing from happening?’ A (white American) poet asks, positioning his words in opposition to his government’s war on Vietnam. Linton Kwesi Johnson (the dub poet and British Black Panther) when asked if poetry can affect such material change replies: it cannot.

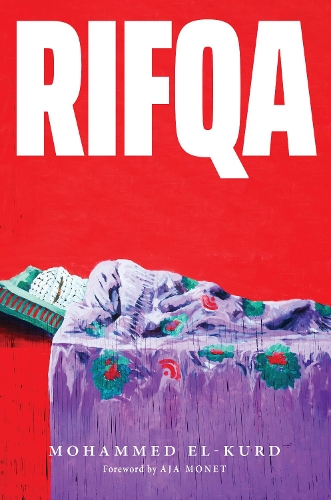

It takes one intimate with the needs of the oppressed – Linton Kwesi Johnson is the child of poor Jamaican immigrants to the U.K. – to know that sometimes it is more essential to defend your neighbour’s flat from National Front firebombs than to write poetry. As Mohammed el-Kurd writes from occupied and bombed Palestine – ‘If Shakespeare / was from here he wouldn’t be writing.’

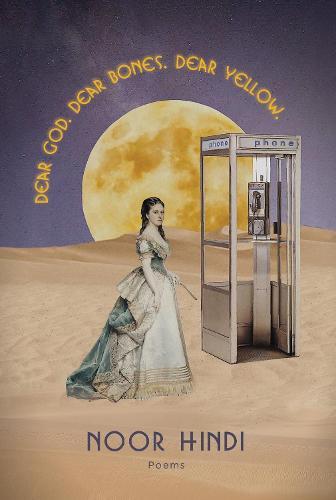

These two young poets, Noor Hindi (born to a Palestinian refugee displaced to another occupied territory: Turtle Island / ‘U.S.A’) and el-Kurd (a Palestinian of Jerusalem, arriving in Turtle Island / ‘U.S.A’ as a university student) traverse the nuances, heartbreaks, and furies of Kwesi Johnson’s ‘it cannot’ in their debut collections, Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow (2022) and Rifqa (2021) (Haymarket Books).

The coloniser is exposed as an omnipresent violence, overt and subtle – ‘Israel’s’ white phosphorus (likely bought from the Americans) sits side-by-side with ‘U.S’ professors fetishising Palestinian ‘trauma.’ They write their poetry against Zionist ‘normalisation.’ The Zionist entity doesn’t just want international – see Global South – states to accept its permanence, but for the colonised’s imagination to as well. ‘Stop telling us how to fight,’ Hindi demands in her breathtaking list-poem titled ‘Palestine.’ The implied repetition of ‘Palestine / is’ enacts the opposite of ‘normalisation.’ It ‘returns to the source’ – to use Amilcar Cabral’s term – that is to say: it orients Hindi to the oppressed, accountably, and stays with Palestine / Palestinians in their dignity and woundedness. Her list is expansive and steadfast:

‘[Palestine is] Occupied / country. Israel has the right / to defend itself. Ahed Tamimi, / ice cream on tongue, [… ] My grandmother, / born ten days before Nakba, [… ] Is queer. Is fuck the patriarchy. […] My father crying / to Omayma El Khalil. Sweet black tea, […] Two state “solution.”

Ridding the coloniser from one’s heart and mind – what Muslim anarchist Mohamed Abdou describes as the ‘jihad’ (struggle) against one’s inner fascisms – is necessary to find the clarity and strength to rid him from the land. ‘We have to find ways to love and support each other [… to] carry [each other…] when we feel like we cannot go another step,’ writes the Black anarchist and former Black Liberation Army member Ashanti Alston. Poetry, it turns out, can be a suitable medium for both tasks.

Poetry can counter interrogate those who demand you be an easy answer to a question only they can ask. Hindi:

‘I want people to stop asking if I love this country […] Ask if it loves me.’ It can be a means to kindle and offer tenderness in an anti-human system. See Hindi’s opening poem ‘Self-Interrogation:’ ‘I – / Need to focus. On something besides. / The rush of migration. […] / The unending sound. Of a newscaster’s voice […] there was a child in a yellow dress reading a poem. / For minutes on end, I could not be indifferent / to anything […] Not the bombs, twisting limbs. Not the cages […] Yes, I used a newspaper to cover my eyes.’

This poem sets up the questions she and el-Kurd interrogate: what does it mean to write in a time of genocide? How do you survive spiritually when the security the oppressor offers resembles a bribe paid in indifference? How can you write against this bribe to strengthen our ability to care for each other and/or resist?

*

For colonised people the place is troubled. With sarcasm, the second part of Hindi’s collection – dealing with the racism of assimilation and border enforcement in the ‘U.S.A’ – is titled ‘American Beings.’ In Rifqa‘s longest poem ‘Where Am I From Jerusalem?,’ what appears to be a proclamation of self possession, ends in a distressed cry for recognition from an occupied city el-Kurd is disappearing with:

‘Where am I from grunts? Where am I from Jerusalem, / from that “State”? / […] from blood on the streets? […] Where am I from forgetting? / […] From hoses raining on a riot?’

For Hindi, the ‘U.S.A’ is an estranged place, of ghosts, of disavowal. The assimilation it forces is counter-insurgent, the end result a numbing to violence. Hindi writes, ‘I know I am American because when I walk into a room something dies.’ This indifference is complicated because this ‘violation’ – the subtitle title of Hindi’s ‘USCIS Trip #3’ – may well be directed towards her family. In the four part prose-poem USCIS trip (United States Customs and Immigration Services) Hindi reveals ‘Americanness’ to be less an ethnicity, more a regime of imperial feeling. The rote repetition of certain phrases – before malign state actors – hoping for a safety that you are by barred from birthright. From ‘USCIS Trip #3: A Test:’

‘I test her [referencing her grandmother’s USCIS citizen test] every week […] She has trouble pronouncing four words: legislature, communism, terrorist, and spangled. […] I repeat them to her: […] legislaturecommunismterroristsspangled / and on and on and on.’ From ‘A Chaos of Semantics’: ‘repetition causes a word or phrase to lose meaning […] / I repeat: / We Too Are American We Too Are American We Too are American […] When I repeat this phrase, my body disappears.’

el-Kurd’s Palestine contrasts as a place in which colonisation is not disavowed and believed to be consolidated (for the Indigenous and Black nations of Turtle Island still resist) but at the forefront of the oppressor’s mind. Palestine is a place of thrown bricks, armed settlers, rubble, burning cop cars and tear gas. Both writers refuse to [feed the Americans] ‘the opposite of guilt’ (Hindi) in presenting Palestine as a tragic, pitiable elsewhere. el-Kurd writes, with a lucidity both hilarious and devastating:

‘I have never once felt free anywhere: / […] not in Santa Monica, the American Tel Aviv; / not in New York, the American Tel Aviv; / Not in Tel Aviv, the American Tel Aviv.’ They are saying: for decolonisation to occur in either place, it must be simultaneous. The imperialists’ spheres of accumulation / repression do not respect national borders, and so neither should our affinities / solidarities. Hindi exposes the futility of reifying / desiring citizenship in a world of transnational empire: ‘My Grandmother is ALIEN. My Father is ALIEN. My mother is ALIEN. I am ALIEN. My siblings are ALIEN. The whole goddamn world is ALIEN.’

Hindi and el-Kurd reject their role as ‘insider’ representatives. Hindi is a reporter and el-Kurd is ‘The Nation’ magazine’s Palestine correspondent. They show representation as a continuum of the rewarded but censored entertainer or demonised but truth-telling threat. el-Kurd quotes Amal Dunqul, ‘If I were to gouge out your eyes / and place gems in their place / would you still see?’ Both poets reject respectable appeals to their oppressor. el-Kurd, ‘At a certain point the metaphor tires at a certain point I’ll grab a brick.’

Hindi writes, ‘We are Muslim & sometimes we joked about blowing shit up.’ This ‘audience’ (embodied in the liberal racist professor asking ‘what does it mean to witness yourself, on television, dying’ in Hindi’s ‘In Which the White Woman on My Thesis Defence Asks Me about Witness’) is pushed beyond comfort by Hindi / el-Kurd’s refusal to play the trope of the passive victim, and into the anxious, by confronting them instead with resistance and/or analyses of irreformable complicity. ‘What comes after awareness? […] a drone […] tax dollars pay for the bombs that kill my people,’ reminds Hindi. The question of ‘audience’ is resolved by whittling interlocutors down through alienation until only those amenable to their self-determination remain. el-Kurd quotes his grandmother Rifqa: ‘We don’t want your sympathy, we want your action.’

*

These poems collapse the distance between grief and defiance, imperial core and periphery, into screams against the enemy, which, when heard by newly demarcated friends, translate to warm, gentle assurances. One gets the sense that for Hindi and el-Kurd recognising that poetry is only words and not a substitute for action, is an act of love – as if to say, we acknowledge what you need and what the world is doing to you, and, though, in our words, we cannot give you this, we hope they hold you, however briefly, however modestly. In a way, acknowledging the limits of poetry becomes the precondition of it being genuinely meaningful. Hindi writes, ‘I love. / Yet we do not solve a single thing. Not / the occupation, a freeze. Not the guns, / […] not the – not the – not.’

*

Silas Curtis is a support worker and poet based in Glasgow. He has published with Prolit, Wet Grain, Overground/Underground, and Propel Magazine. He is currently studying an MLitt in Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow.