Prose choice

Previous prose

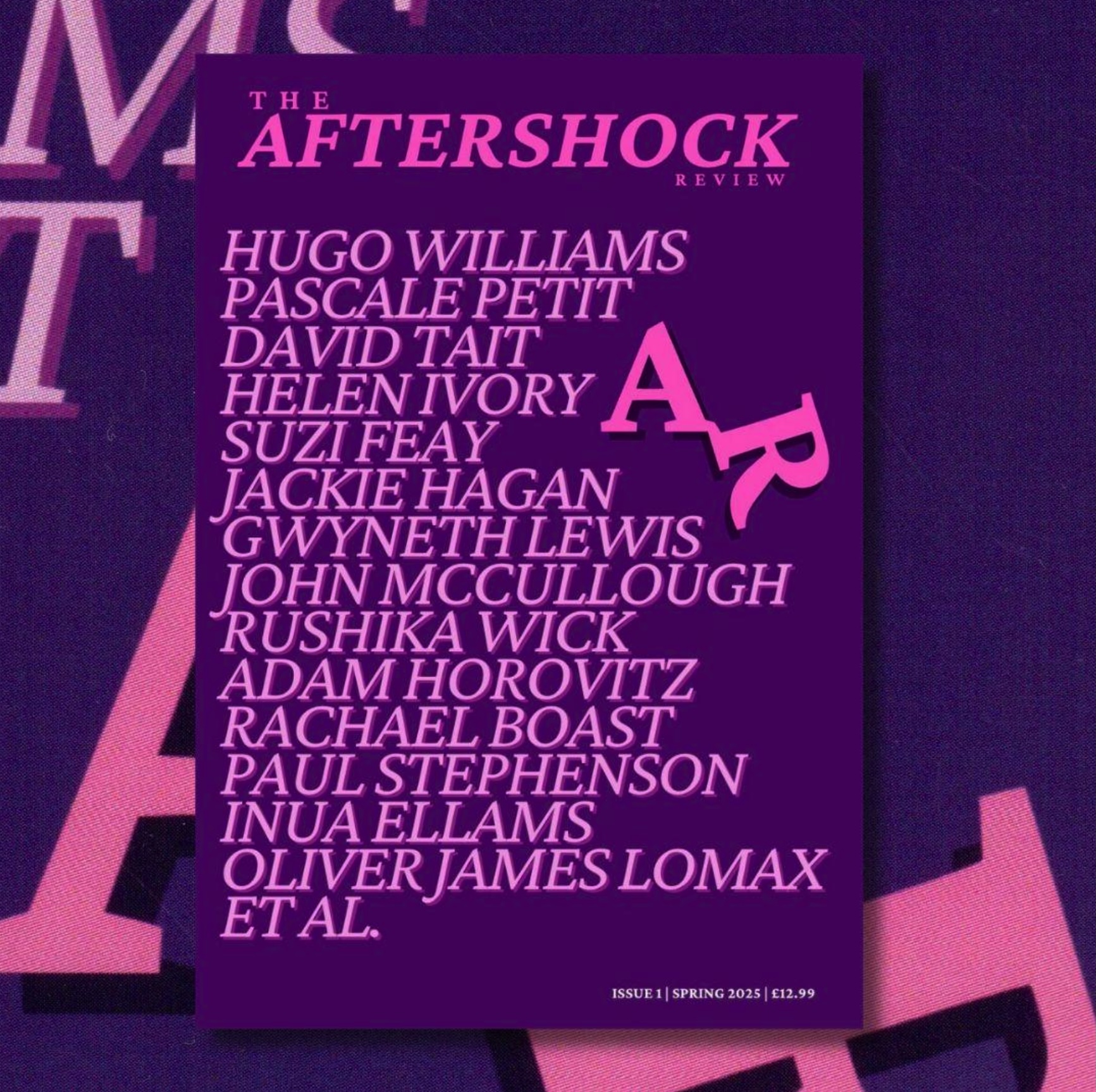

Max Wallis on ‘The Aftershock Review’ for Mental Health Awareness Week

What Happens After the Aftershock?

In February 2024, I took an Uber to a bridge in London. I was planning to die.

Instead, I got out and walked to St Paul’s, where I was detained and sectioned. I remember the shame. The dizziness. I remember thinking I’d already lost everything that mattered: my flat, my mind, my relationship, my future.

Two days later, I fled London with nothing. Not even my sanity to hold me.

Back in Chorley, Lancashire, in the room I grew up in, I lay in bed with PTSD, trying to work out how to stay alive. I was thirty-four, living with my parents, unable to do the simplest things. For a long time, I couldn’t read. I couldn’t cook. I couldn’t bear the sound of my own thoughts.

But slowly, I began to imagine something new. Not a return to who I’d been, but a project that might help me stay. A poetry journal. Something honest. Something that wouldn’t look away. Something I hadn’t yet seen in the world.

I didn’t set out to start The Aftershock Review. I was trying to keep going, hour by hour, imagining a space for work that didn’t feel safe elsewhere. A place for voices I rarely saw platformed, poets who were ill, grieving, disabled, burnt out, or excluded from traditional publishing routes. Could I make something that didn’t demand polish or performance? Could I build something that made people feel less alone?

The first issue of The Aftershock Review features over fifty poets, from emerging writers to major names. Some are publishing for the first time. Others, like IS&T’s own Helen Ivory, Hugo Williams, Pascale Petit, Inua Ellams, Gwyneth Lewis, have long, celebrated careers. But every poem was chosen because it speaks to something true. The urgency of survival, the defiance of showing up, the beauty that can exist after devastation.

The past year has been a reckoning in every sense. It’s also been a revival, and a return to my first and truest love: poetry. I’ve been hospitalised. I’ve been trapped. I’ve lived as an addict and an alcoholic. And I’ve been lucky. I’ve had support. And most of all, love in the form of family I thought I was estranged from and a poetry world that welcomed me back with open arms. As Don Paterson wrote, “Falling and flying are near identical sensations, in all but one final detail.” Poetry helps me remember which one I’m doing.

The Aftershock Review is built around access, care, and community. When our crowdfunder launched, I didn’t expect the outpouring of support we received. That collective belief didn’t just fund the issue, it helped me recover. It reduced my PTSD symptoms, bit by bit. It gave me a sense of purpose again. There’s a strange and beautiful power in being witnessed.

As of March 2025, we have raised £7,124. It also makes possible what we’re planning next: pamphlets, events, outreach, and the long-term goal of The Aftershock Society, a press for poetry that we hope will reshape the literary landscape entirely.

We believe trauma speaks many languages. It whispers in the quiet of a bruised room, echoes in waiting rooms and hospital corridors, and lingers in the smallest details: a Tupperware box, trying to find a pin in a sharps box in the hospital to change your sim card, a laugh that arrives like a bear hug. Poetry lets us hold all of that, not to solve it, but to name it, sit beside it, and sometimes, transform it.

In The Aftershock Review, we’ve published poems that move through grief, illness, psych wards, addiction, love, loss, and laughter. Joseph Fasano reminds us, “The amount of agony / you carry / is only the vastness of your / love / waiting in the darkness to be found.”

There are wounds that don’t fully heal, and some that reopen again and again. But I believe we can still write from them, not despite the damage, but because of it. Through poetry, we find other ways to breathe. Other ways to keep going.

Mental health is not separate from this work. It is threaded through every page. This magazine wasn’t made in spite of illness. It was made from it, with care, with attention, with time.

This is The Aftershock Review, a journal built in the aftermath. A home for poems written when everything else was falling away. A place to say: you are not alone in this. You never were.

Max Wallis is the editor of The Aftershock Review which launched this spring. To buy, to submit to, to contribute to the crowdfunder, please click here: https://www.aftershockreview.com/

Kate Venables

A Strange Madeleine My paternal grandfather was a dentist and set up his practice before the First World War in his parents’ home at 222 Linthorpe Road in Middlesbrough. The house had a workshop at the bottom of the garden for the dental...

Morgan Harlow

The Noise Outside That day, on the patio, you heard a noise and you jumped up, ready to act, while I just froze, telling the story again and again to your mother, her lover, everyone knew that you were brave and I just froze, my sister, my dad, a...

Kate Rigby

The Long Grass They’ve just kicked it into the long grass, one politician says to another on TV. I tune out from the others sitting around me at Tree Tops. I feel it now, that long grass, cool and welcome, at the far reaches of the playing fields...

Andy Raffan

Skipping the Light Fantastic ‘You’d never believe it to look at her, but there goes Rita Pulaski, World Jump Rope Champion nineteen fifty-six,’ my grandmother said, pointing a pudgy finger at the window. ‘Really? Her with the two sticks?’ I said,...

S. F. Wright

RAWSON, ARGENTINA Donald’s father was a plumber, his mother a homemaker. As a child, Donald considered his mother’s existence—cooking, cleaning, doing laundry, taking care of Donald and his younger brother—empty. He didn’t think much of his...

Louella Lester

Marking Your Territory It was a pack I’d never seen in my neighbourhood before. A panting bulldog and a big-eyed mutt, with a handsome guy in tow. We were all waiting to cross the street, them on one corner, me on the other, when the guy,...

Phoebe Thomson

Friendly Shriek of bats, in the barn’s rafters. Wild. Sweet and sour smell, our sweat, our blankets, our hay. Pebbles whickering, the clatter of her week-old foal, its brittle legs. Tired. Not-long back to sleep. More light. Later. Rain on...

Fiona Perry

The Mirror Eimear’s half-brother, Julian, died and left her a terraced house. I offered to help Eimear clear the rooms and to do runs to the charity shop with anything worth passing on. We discovered that he had amassed about a hundred...

Harlan Yarbrough

An Orphan’s Progress Geoffroy, no longer young and a man of importance, could have ridden in a luxurious coach. He chose to walk, because he enjoyed walking. If Zarafa was going to walk he would walk with her. No strolling,...