This questionnaire comprised part of my Masters’ independent research project on ecopoetry. Our climate emergency is evidenced in increasingly devastating weather events and yet, there is still resistance to altering our behaviours, to challenge the destructive effects of neoliberal economic practices and imperialism on our ecosystems. I believe that ecopoetry needs to speak both to those willing to listen, and to those who are resistant to doing so. Therefore, I argue that a variety of poetic voices and approaches are needed, to enable people of all opinions, to hear ecopoetry’s call to action. Craig and Helen’s excellent work is varied in approach and often experimental, and provides two, distinctive voices and perspectives from different areas of the world. I hope that their insights will enthuse and inspire you, as they did me.

– Kathryn Alderman

Ecopoetry Discussion with Helen Moore

1. Could you tell me your thoughts about what ecopoetry is and how you might define it?

I define it as poetry written with the consciousness of our interdependence with all beings – and not just the so-called charismatic megafauna, I mean Flies, Slugs and Earthworms too! I follow William Blake’s sense that everything that lives is holy, and for that reason I want to raise all more-than-human beings from the margins to which Western culture has relegated them. Ecopoetry is also written from a deep sense of the particularities of place, and awareness of the intersecting social and ecological crises we face, and is an important strand of the emergent regenerative culture, which has the capacity to nurture and create active hope for the future.

Ecopoetry can remind us that we too are Nature, that we’re not separate or superior, as we have been conditioned to believe. Ecopoetry can help us see the world with new eyes, to feel awe at the 4.6 billion year-old Gaian superorganism which is our home and our wider body. Also, to understand that in harming Earth, we are harming ourselves.

And in the same way that the ancient bards inspired their warriors, ecopoets can inspire others to creatively resist the forces of destruction, whilst also seeing possibilities for healing and transformation. This is a big endeavour. But I have had glimpses of how my work has sown seeds of an ecocentric consciousness in others, and this humbles me and supports my sense of purpose/vocation.

2. Would you say there is an ecopoetry form – perhaps in terms of structure, devices, language and means of expression for example?

I have long been inspired by the opportunities of poetic form and my work is expressed with a strong relationship between content and form. Fundamentally I agree with Forrest Gander and John Kinsella in Redstart, An Ecological Poetics:

‘A poem expressing a concern for ecology might be structured as compost, it might be developed rhizomatically, it might be described as a nest, a collectivity. Its structure might be cyclical, indeterminate, or strictly patterned. The formal possibilities are as infinite as ever since there isn’t any formal structure for representing ecology or nature. And writing is a constructed system.’

In writing about landscapes, I generally choose long-form ecopoetry to create a collaged and cumulative experience, which reflects the multi-layered palimpsest of the place I’m expressing and creates a sculptural bio/tapestry that reflects different elements of a particular landscape. The various sections can juxtapose perspectives and voices, such as human/more-than-human. These different poems in a sequence may also develop a thematic interpretation, and can take the reader/audience on a journey from familiar into less familiar territory.

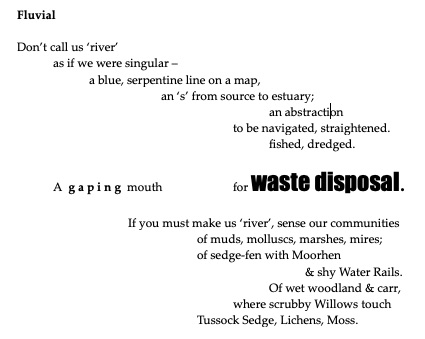

I am also very interested in language and how its use can reinforce modes of perception and behaviour which separate humans from our wider Earth body. For example, my work often explores other ways of expressing interconnection. This is an extract from my most recent long-form ecopoem, ‘Dorset Waterbodies, a Common / Weal’ (2021):

3. Would you say that there’s a difference between nature poetry and ecopoetry?

Ecopoetry for me is all about consciousness. Consciousness of our deep interconnection with our planetary home and of our humanimal nature. Awareness too of the paradigm that has created our disconnection in Western cultures, and the power structures that have a vested interest in maintaining our disempowered state.

Of course, consciousness is evolving all the time, and I would say that in the Western tradition in recent centuries, ecopoetry has evolved out of Nature poetry – although the oral poetries which our indigenous ancestors made would have expressed culturally conditioned versions of the Gaian consciousness we are currently trying to reclaim. Poets continuing to write about ‘Nature’ nowadays may continue to see it as ‘other’ and lack awareness of/be unwilling to express the socio-political dimension, which I feel is inseparable.

4. Would you be able to define your own form(s) of poetry and yourself as a poet?

There are many different definitions of ecopoetry and with them various principles. Central to my work are four thematic strands, which are: reconnection with more-than-human Nature and our wild humanimal selves; witnessing ecocide and intersecting social injustices; resistance, speaking truth to power; and visioning Earthcentric ways of living and being. For me each is a portal through which ecopoetry can be developed, and they are of course also interconnected.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been going deeper with the ‘reconnection’ strand by describing an ecopoetic practice which I call ‘wild writing’, delineating a methodology through which to inspire others. ‘Wild writing’ is an essential part of my work as an ecopoet, as it enables me to open myself to become a channel for expressing more-than-human Nature. In this I’m influenced by the great American ecopoet, Gary Snyder, who said: “My political position is to be a spokesman for wild Nature. I take that as my primary constituency.”

In practising ‘wild writing’ the principle of ‘co-creation’ is paramount. In our culture we’ve been conditioned to think of the act of creation as happening almost in a vacuum. We’ve tended to think of the creative genius (white, male) working in isolation, though possibly inspired by a female muse figure. In reality, everything happens as a co-creation. A tree doesn’t grow in a vacuum, but responds to light, air, soil, water, weather, insect colonies. It interacts with other trees through mycorrhizal relationships. A tree is also home to birds and other creatures, who may have a symbiotic relationship with it, such as eating its berries for nourishment, and then disseminating its seeds through their droppings.

Co-creation is at the heart of all experience – all beings are infinitely connected through the web of life, ecosystems and communities we inhabit. As humans, our co-creation is with other humans, including the writers who inspire us, and with more-than-human beings as an interspecies experience. Co-creation may also involve working consciously with the Universe, the Divine, Spirit, Oneness, God, whatever we may choose to label this dimension.

5. What made you choose your chosen form(s) of poetry and when did you begin writing it?

The root of my participation in the ecopoetry movement lies in my initiation as Bard of Bath in 2003 via an annual competition in the city of Bath in Southwest England. The role draws on the oral traditions of the ancient Celts, their bards employed by monarchs and chieftains to combine a range of communicative modes, including storytelling, poetry and music, recording histories and genealogies, lamenting, and spurring warriors into battle. Exploring and inhabiting this tradition within a modern context over the course of the year and a day that I held the title gave validity to my desire to express my earth-based spirituality in what I was experiencing as a rather secular literary world, and helped me to broaden my perception of the role of the poet.

At the same time, I was becoming acutely aware of the climate crisis, widespread ecological destruction and intersecting social issues, and wanted to use my creativity to learn, witness, respond, communicate. Consequently, I decided to dedicate myself in service of Gaia and future generations. Although I haven’t had children, I started to feel for how their lives will be impacted by insufficient collective action.

As I began to see that the work I was making was ecopoetry – even though the movement was barely known in this country – several poets I knew tried to warn me not to limit myself with this label. I recall one older white male poet, whose class I was attending at the time, telling me: “there’s nothing new to write about nature,” with the implication that my poetry was anachronistic, harking back to the Romantic tradition.

However, defining my writing as ecopoetry felt like a statement of intention to stand in the world with the consciousness of all that was at stake, and in acknowledgement and celebration of our deep interdependence with all beings, of the miracle of life on Earth. My use of the term has also been about cultivating a practice of observing and opening to more-than-human Nature, no longer seeing it as ‘the environment’, or the background wallpaper to my life. But as sentient, having intrinsic value, and offering an enriching reciprocity as mother, muse, teacher, lover. And I evolved the aspiration to raise the status of more-than-human beings from the margins to which industrialised Western cultures have relegated them.

6. Have any other poets’ work or any poetic theories been influential to your own practice?

Major influences on my work have been the American Beat Poets, in particular Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder. Opening the collected works of Ginsberg in the early Nineties blew me away, put me in touch with the radical edges that poetry could embrace. Snyder’s ecopoetry has also been a guiding light for many years. I’m a massive fan of his worldview, the perennial wisdom shaping his poetry, and regularly return to drink from the source through books such as Earth House Hold (1969) and The Real Work: Interviews & Talks 1964-1979.

The work of Suzi Gablik, particularly her books Has Modernism Failed? and The Re-enchantment of Art have also been instrumental in helping me to gain perspectives on the dominant culture, and to have the courage to stand for something different. And I have already cited Forrest Gander and John Kinsella’s ecological poetics as an influence.

Other poets from whom I’ve imbibed deeply include Rumi, Blake, Rilke, Shelley, Neruda, Yeats, Patrick Kavanagh, Francis Ponge, Kathleen Raine, Robert Bly, Denise Levertov, Audre Lorde, Carolyn Forché, Heathcote Williams, Alice Oswald, Joy Harjo, Jorie Graham, Anne Elvey and Anne Casey. Niall McDevitt, a London-based Irish poet, whom I knew personally for some years, was a great influence when I’d just found my voice, and I’m grateful for his encouragement to take my poetry seriously. I admired how edgily political his own work can be and our connection influenced my first collection, Hedge Fund and Other Living Margins, which came out in 2012.

I also want to honour my friend the late Jay Ramsay, a British poet and psychotherapist, who advocated for spiritual vision in contemporary poetry. He co-edited (with Andrew Harvey) Diamond Cutters: Visionary Poets in America, Britain and Oceania, an anthology which came out in 2016 and includes a couple of my poems. And I am indebted to the Italian ecopoet Massimo D’Arcangelo, a kindred spirit and great friend, who has championed my work to an Italian audience. INTATTO/INTACT, our bilingual Italian-English book of ecopoetry, co-authored with the Australian ecopoet Anne Elvey, was published by La Vita Felice in 2017, and was a fascinating project in responding to and weaving together our three voices.

7. Do you have an imagined reader or readers in mind and how would you like them to respond to your work and to ecopoetry in general?

I have always seen myself as a champion/cultural ambassador of the Green Movement, although of course there are many ‘Greenies’ who may not read poetry or be familiar with my work. Nevertheless, I want to represent the emergent ecological consciousness in Western society, and given that there has been a pushback from traditional publishers and other poets/literary gatekeepers, it has felt important to discover new audiences at green events and festivals, such as TimberFest in the National Forest, where I shared my work in July 2021. I am also grateful that my ecopoetry is quite well known in academic circles, and have appreciated opportunities to share my work and ideas to students. I feel that I have a lot to communicate to young people in particular, and it was gratifying to find my work well received by young Italian poets when I gave a keynote lecture at PoesiaEuropa in September 2021, and to spend time in dialogue with them.

Also my work has often been made in relationship with the communities in which I’ve lived, and in solidarity with activist endeavours. For example, my ecopoem ‘Findhorn Bay, Waves of Flow & Flight’ (2018) was written as part of the Waves O’Flight Community Art Project, a group celebrating the wildlife of Findhorn Bay, a large tidal estuary, on the Moray coast in NE Scotland. I researched and wrote this piece having lived in the area for a couple of years, and as part of my engagement with a community group trying to stop the shooting of wild Pinkfooted Geese in what is actually a nature reserve. I performed my piece to a packed audience during the Findhorn Bay Arts Festival 2018, and subsequently collaborated with VisionSonic to make an audio recording with soundscape.

8. Do you craft your ecopoetry with different types of readers in mind, or is your means of expression informed by the idea that you wish to convey perhaps?

Seeing my work as 2D sculpture on the page, I am excited by developing this visual aspect to make my ecopoetry more engaging for the general public. In my most recent project – the long-form ecopoem ‘Dorset Waterbodies, a Common / Weal’ (2021), exploring impacts of pollution and climate on the Poole Bay watershed – I placed text installations in gallery spaces and used windows and walls as pages to create a dialogue between inner and outer worlds. An example is this overturned churn with ‘spilt milk’ and handwritten lines (‘Nightmare Slurry Spill’, from ‘Dorset Waterbodies’).

Installation at the RiverRun exhibition, Durlston Country Park, October 2021

I have also collaborated with filmmakers and sound artists to share my work through multimedia modes, again with the intention to reach new audiences. An audio recording of ‘Dorset Waterbodies’ was playing on a loop in the two galleries in which my work was installed over the past couple of months (Durlston Country Park, Swanage, and Lighthouse in Poole). One visitor emailed to tell me that hearing and reading my poem was a moment he would never forget. He is currently establishing a group of Water Guardians to monitor river pollution in Wiltshire, and wanted to share my poem with his fellow activists, which he was able to do via my SoundCloud (Helen Moore Ecopoet).

9. How do you think that ecopoetry can resist the causes of our climate emergency and can it have a positive, real-life influence on people’s behaviour?

All my ecopoems have been made with awareness of the context of white supremacist, patriarchal, imperialist, industrial capitalism, which sees the Earth (land, wildlife, soil and seas) and most of her peoples as a resource to endlessly exploit. The multiple intersecting social and ecological crises we collectively face, including the climate crisis, are the logical consequence of this rapacious economic system and the global elite who perpetuate it.

Within this context I also see my own experiences of insecure housing within a private rental market with little tenant protection; of being a migrant; of being dispossessed; and my yearning for home/a place to put down roots. Whilst all these experiences have been deeply challenging at times, I simultaneously acknowledge that my spiritual and creative practices have strengthened me and given me the courage to continue, and I know that expressing this in my work has inspired others in different ways.

Seeing the bigger picture, the multidimensionality of our lives, also leads me to perceive how at a deeper level than our ecocidal socio-economic system, at the very roots of these intersecting issues, there is a crisis of perception and imagination. And for this reason, ecopoetry has something important to contribute.

10. How should poets best address the harmful effects of neoliberal economics and colonialism and how might they bring in the voices of peoples from those colonised nations?

As a white British poet, I have a responsibility to understand the colonial histories which the people of this land perpetrated, and in which they have been entangled through state-sponsored transportation/emigration. The Australian poems in my third collection, The Mother Country, evolved from my independent explorations of the site of ‘first contact’ in Sydney to try to understand how it might have been prior to British invasion, including aspects of local indigenous Australian cultures, particularly the Cadigal people, and the wild ecosystem.

I discovered old Moreton Bay Figtrees and pictured them in my mental reconstructions of the pre-colonial landscape. I read accounts of the early years of the British colony made by the British officers who came with the first fleet of ships, their experiences of Aboriginal peoples, and their attempts to understand local languages. I also discovered everything I could about contemporary indigenous cultures in the area, from Aboriginal writers, dancers, poets; and immersive experiences such as site-specific theatre and going on ‘bush tucker walks’ to learn about native wild foods.

‘Biophony, Prior to Invasion’, which is the opening poem of the collection, imagines the Sydney harbour area – known in the local Dharug language as ‘Waran’ – one year before the British landed. I focus on the wild sounds of the ecosystem, using the term ‘biophony’, which white Western ecologists have taken up to describe the soundscape created by animals, insects and birds, but which according to them, excludes human voices. By returning indigenous people to the imagined context, I question this position. However, I am conscious of taking care not to appropriate the voices of colonised peoples, and in my poem ‘A British Marine Officer Considers the Colonial Presence, Ventriloquising the ‘Natives’’ I deliberately play with this position.

11. What advice would you offer to poets wanting to write ecopoetry?

I would advise reading other ecopoets, examining personal privilege and how that might influence imagination and perception; and developing an awareness of the root causes of the intersecting social and ecological crises. Also I would suggest developing a wild writing practice and embodying a sense of oneself as ‘humanimal’.

Helen Moore is a British ecopoet, socially engaged artist, writer, Nature educator and facilitator of outdoor wellbeing programmes. She has published three ecopoetry collections, Hedge Fund, And Other Living Margins (Shearsman Books, 2012), ECOZOA (Permanent Publications, 2015), acclaimed by the Australian poet John Kinsella as ‘a milestone in the journey of ecopoetics’, and The Mother Country (Awen Publications, 2019) exploring aspects of British colonial history. She offers an online mentoring programme, Wild Ways to Writing, and works with students internationally. In 2020 her work was nominated for the Forward and Pushcart Prizes and received grants from the Royal Literary Fund and Arts Council England. In 2021 Helen gave a keynote lecture on ecopoetry and landscape at PoesiaEuropa in Italy; and she collaborated with Cape Farewell in Dorset on RiverRun, an ecopoetry project drawing on fieldwork and research from scientists and farmers in Dorset to examine pollution in Poole Bay and its river-systems.

www.helenmoorepoet.com

************

Ecopoetry Discussion with Craig Santos Perez

1. Could you tell me your thoughts about what ecopoetry is and how you might define it?

I define ecopoetry broadly and simply as poetry about nature, water, wilderness, ecology, animals, agriculture, waste, environmental justice, the anthropocene, food, climate change, and more.

2. Would you say there is an ecopoetry form – perhaps in terms of structure, devices, language and means of expression for example?

I would say there an aesthetic diversity to ecopoetry, which reflects and embodies the bio-diversity of planetary ecologies. Ecopoetic forms can include the pastoral, necropastoral, eclogue, lyric, narrative, epic, elegy, documentary, modernist, postmodernist, sonnet, haiku, collage, hybrid, list, ode, and more.

3. Would you say that there’s a difference between nature poetry and ecopoetry?

I usually conceptualize nature poetry as a subset of ecopoetry. However, there are more often defined as different in the sense that nature poetry is about a romantic conception of the natural world as a place of tranquility, reflection, and transcendence, whereas ecopoetry is about human interaction with ecologies as entangled, contaminated, and transcorporeal.

4. Would you be able to define your own form (s) of poetry and yourself as a poet?

I would define myself as an indigenous Pacific Islander postmodern, decolonial, diasporic, and eco-poet. I consider myself an experimental poet because I experiment with different forms ranging from the avant-garde to the traditional.

5. What made you choose your chosen form (s) of poetry and when did you begin writing it?

I began consistently writing poetry as an undergraduate student. I attended college and graduate school in California. I was very influenced by the history of poetry and poetics in California, including the Beats, the Language poets, the Multicultural poets, the Deep Nature poets, The Black Mountain poets, the San Francisco Renaissance, and more. Reading all these diverse poets influenced me to choose to be experimental.

6. Have any other poets’ work or any poetic theories been influential to your own practice?

Besides the aforementioned poetic movements, I have most deeply been influenced by Indigenous poets, especially Native American and Pacific Islander poets. Some of these include Joy Harjo, Simon Ortiz, Haunani-Kay Trask, Robert Sullivan, Albert Wendt, N. Scott Momaday, and Allison Hedge Coke.

7. Do you have an imagined reader or readers in mind and how would you like them to respond to your work and to ecopoetry in general?

I usually do not have an imagined reader(s) in mind when I write. In general, I would like anyone who reads my work to respond in a way that they would feel engaged by my ecopoetry in a way that will nourish and cultivate their own eco-consciousness.

8. Do you craft your ecopoetry with different types of readers in mind, or is your means of expression informed by the idea that you wish to convey perhaps?

I craft my ecopoetry mainly informed by the ideas and emotions I am hoping to convey. However, there are times when I write ecopoetry for specific environmental events, conferences, agendas, marches, etc; when that is the case, I do craft the poem with that particular audience in mind.

9. How do you think that ecopoetry can resist the causes of our climate emergency and can it have a positive, real-life influence on people’s behaviour?

On a personal scale, I think ecopoetry can help the author reckon with eco-anxieties and fears and empower the author to become more involved in the climate justice movement. I also believe that ecopoetry can educate readers on environmental issues and inspire them to live more sustainably and to become active in environmental movements. Ecopoetry can be a creative tool to develop environmental literacy and a more human and emotional form of climate communication.

10. How should poets best address the harmful effects of neoliberal economics and colonialism and how might they bring in the voices of peoples from those colonised nations?

I don’t think there is a “best” way to address neoliberalism and colonialism; instead, I think that all poets should try their best to address these important phenomena. Poets should learn about the harmful impacts of capitalism and imperialism and write about what they learn in their poems—that way their readers can learn as well. I don’t necessary think that poets need to bring in the voices of poets from colonized nations; instead, I think it important for poets from the Global North to read, teach, and support authors from the Global South.

11. What advice would you offer to poets wanting to write ecopoetry?

I would offer two main pieces of advice. First, spend as much time as possible in nature. Go hiking, walking, swimming, exploring. Go to the beach, ocean, river, forest, mountain, garden. Write outside. Try to capture and describe all your senses. Second, write from the place you live. As you write locally, try to make connected to the global, highlighting interconnections and intimacies.

Craig Santos Perez is an indigenous Chamoru from the Pacific Island of Guam. He is the author of five books of poetry, most recently Habitat Threshold (2020), a collection of eco-poetry. He is a professor in the English Department at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa.

************

Kathryn Alderman is studying for a Masters in Creative and Critical Writing at the University of Gloucestershire. She’s widely published, including in Ink Sweat & Tears, 14 Magazine, Atrium Poetry and in the forthcoming Dear Politicians ecopoetry anthology. She won Cannon Poets’ Sonnet or Not competition and is runner-up in the 2022 Gloucestershire Writers’ Network poetry competition, and will read with fellow winners and poetry judge, Adam Horovitz, at the Cheltenham Literature Festival, 9th October 2022. She recently won the 2022 ‘Gloucestershire Prize’ in the Buzzwords Poetry competition judged by Nigel McLoughlin. Twitter: @kmalderman1 and Instagram: @k_m_alderman