This poet has a talent for transforming the familiar world through the power of her imagination and, moreover, doing so in plain, down-to-earth language. Things are personified and persons are thingified, as in the poem ‘Ironing’, which reaches far beyond the ordinary domestic chore of its title. Is a clothes iron speaking as a person or has a human being become an iron?

Today I confront a shirt

If I sit still

I could create a burn mark.

But being energised through my tail,

I just have to move ahead

along the blue stripes.

This poem shows Yuko’s idiosyncratic vision of the world but also the quiet discontent with gender roles that runs through her poetry. The iron is fulfilling the traditional wifely task of pressing a man’s shirt but sets about it with a degree of violence. Still, the iron seems to end up as the loser in this controlled struggle and the shirt the victor:

I fall through the dark. […]

The shirt is set free.

It raises its arms like a winning runner

and flies as fast as I drop.

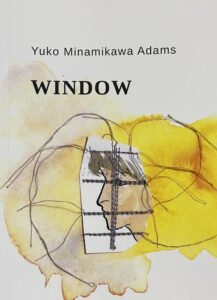

Here I admit I have known Yuko for many years, since she is an active member of the Poetry ID group in Letchworth, England, where she has brought a surreal approach to the writing workshops. Window is Yuko’s first poetry collection in English after a few publications in Japanese.

Gender relations and gender roles may be the main themes of this book, expressed in the author’s typically deadpan way. In ‘Berlin Wall’, the female speaker sometimes takes a submissive attitude towards her male partner (the ‘east side of me’, which could be a play on Asian stereotypes). However, there is also an adventurous ‘west side of me’ which excites him but could also, if the woman is not hugged in return, lead her to ‘forget your warmth,/ step out of your territory,/ make a living without you.’

One extraordinary poem, ‘Chest of Drawers’, traces the social conditioning of gender back into childhood. The opening lines are striking:

My mother is a chest of drawers.

She is multilayered.

Her interior is lined with underwear.

When I was unborn,

I was free to travel between

men and women.

Within the maternal body (probably representing early childhood as well as the literal uterus), the baby girl is free to move, but there comes a point when the mother ‘ejects’ the growing child and locks the drawer of men’s underwear. The mother, apparently following tradition, leaves her daughter in a socially limited role which doesn’t quite fit her: ‘But the bras and knickers are still/ too baggy for me.’

As well as the highlighted social tensions, there is a countervailing trend of reconciliation running through Yuko’s work. The speaker in ‘Berlin Wall’ appears to toy with the idea of leaving her male partner but they still manage to bump along together. And in ‘Different Skies’, it is the art of poetry itself that brings people of different backgrounds, interests and tastes together.

We hear different sounds:

One listens to a cat’s purring

One is drenched with church music.

One overhears sirens from a police car.We gather from different directions

to the one single table.

This poem summarises the spirit of the poetry workshops mentioned above. And it is an example of Yuko’s skill in lyrically uniting disparate elements, sometimes harmoniously and sometimes to startling effect.

Window available from yukominamikawaadams.wordpress.com for £7.00

Dennis Tomlinson lives in London and has been published in many magazines and on websites. His poetry pamphlets are Sleepless Nights (Maverick Mustang, 2019), Over the Road (Dempsey & Windle, 2021) and Ornaments (Paekakariki Press, 2022). He was also co-editor of Hans Sahl in Translation (Independent Publishing Network, 2023).