“For the leadwood trees of Mmadikola. Ya matswere a Mmadikola” is the dedication that award-winning New Generation African poet TJ Dema offers at the start of this excellent chapbook to a species of tree found in southern Africa. Indicating the timber’s properties, the utilitarianism of the English common name “leadwood” reveals the resource hungry worldview of colonisers plundering places such as Botswana – where the speaker’s grandfather works the fields, and even in a child’s giggle “the old syntax is not quite undoing of veldt”.

Inventive, tender, witty and powerfully engaged, an/other pastoral then opens with a prologue distorting Eliot’s famous line, “the word is the cruelest flower”; and in listing further botanical names – “english broom, white snakeroot,/an angel’s trumpet” – TJ Dema establishes the often less familiar context of the colonisation of nature, while various poems reveal other enduring legacies of empire.

A subtle intertextual dance with The Waste Land surfaces through references to the burial of the dead on the sea floor; the elements of water and fire – drowning while crossing water, and forest fires in the Gulf of Mexico and the Amazon – as well as poems resonant with multiple voices. A rice plantation owner barking staccato orders; children crying out from the polluted wasteland (“For we are but bread for the birds,/dead before our very breath is heard”); Brianna employing the colloquialisms of her enslaved African heritage to subvert the perspectives and policies (public health) with which privileged white people target her and her community.

“What was left of understanding between us/was only ever a paper boat. Now half wet/with each crossing.” In this poignant metaphor, the elusive aspects of language and different cultures are evoked. Words of the coloniser, “the TV lady”, the canon. “Your English too sheathed/ to speak and mean at the same time.” Yet Dema delights in wordplay and bilingualism – a riddle translated from Setswana exquisitely describes a cow, and the speaker’s young son effortlessly acquires words in his second language. And we are reminded of an often forgotten dimension of language: “all nature speaks if we listen/oak, pine, bracken, sheep, eel,/ human.”

Borders are another theme, the artifice enforced by the immigration officer and the mind – “here is the line between man and man/and nature/manmade as all false boundaries are.” A song to a cockroach, “nocturnal hisser, rosewood tinted pest, pet”, playfully points up the division between species possessing “ecological charisma”, and those without it. Going back “to where you came from” becomes even less possible when seen within its microbial context, while the “beginend” of a forest and “its flycatchers” “troutlilies” and “lichen” are the commons that no one really owns. Among the aisles of a grocery store the presence of a black bear further erodes boundaries between human and nature in a world of climate chaos as the bear discovers inside her ‘counterfeit den’ the coolness that is absent outdoors.

Having quoted from Achille Mbembe’s Necropolitics in an epigraph to the chapbook, Dema no doubt resonates with Mbembe’s insights into the symptoms and causes of social and ecological breakdown. Seeing bankers and politicians as having nothing significant to offer, a poem senses how division is perpetuated: “we set it up so that it’ll always be a pandemic / Virus or fire / colour or body / Plenty of nothing”.

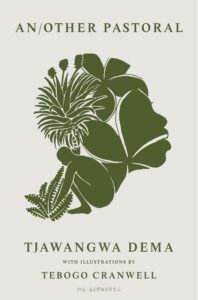

Yet through poems unafraid to sketch division, destruction and oppression, there are brushstrokes of love, grace, joy. The alternative vision of an/other pastoral starts in the heart of a mother willing to give everything for her son (including learning to swim, no doubt literally and metaphorically, despite her experience of a near-drowning as a child). Then, in the final celebration of “good news” which is “youyouyou” “who are alive now”, the chapbook comes full circle with the regenerative promise of the Grail legend underpinning Eliot’s Waste Land, as we sense a future based in interconnected thriving. And this cumulative message of TJ Dema’s finely crafted ecopoetics is amplified through Tebogo Cranwell’s four monochrome illustrations, which beautifully fuse the human body with water, flower, tree, fire, bird, cow.

Helen Moore is an award-winning British ecopoet with three collections, Hedge Fund, And Other Living Margins (2012), ECOZOA (2015), acclaimed as ‘a milestone in the journey of ecopoetics’, and The Mother Country (2019) exploring British colonial history. Helen has shared her work on international stages, including India, Australia and Italy. She offers an online mentoring programme, Wild Ways to Writing, which guides people on a creative writing journey into deeper Nature connection. Her work is supported by Arts Council England, and she has recently collaborated on a cross arts-science project responding to pollution in Poole Bay and its river-systems. Find her at www.helenmoorepoet.com.