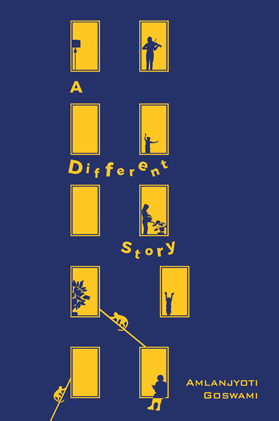

Poet Amlanjyoti Goswami’s third collection of verses, A Different Story (Poetrywala, 2025), conjures a subject that resists acts of dumping trauma, instead alchemizing them into dry humor and decorous irreverence, sans complacency or arrogance. This curious poetical subject, also capable of juggling dimensions of the planes of its experience, often spatializes time and temporalizes space. The book’s sprawling embroidery—of striking paradoxical memories, fleeting cultural homages, self-derisory nostalgic detours, and mild metaphysical subversions—oscillates between universally resonant and deeply personal experiences. Goswami’s style is fragmented. But the poetical subject is probably not so. This is not a contradiction. For this was the precise modus operandi of the modernists and feminists—Emily Dickinson, T.S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Ezra Pound, Katherine Mansfield, Sukanta Bhattacharya, Jibanananda Das, Gauri Deshpande—or the mystical Nalini Bala Devi. Goswami’s protagonists—Justice Fali Nariman, Ustad Rashid Khan, whimsical art filmmakers including a bohemian recreator of Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, Krishna and Arjun, tea sellers, railway personnel, Ritwik Ghatak, Michael Madhusudhan Dutt, New Yorkers and Ahomiyas, Annapurna Devi, Jahan Ara, Karna, Banalata Sen, Parveen Babi and Danny Denzongpa, sadhus and wandering philosophers—are not real and yet not projections of a poet’s lyrical delusions; they are experiences that refuse to be pinned down on a plate of static ideological halides and emulsions. They enchant and trouble us. More importantly, they entice us to undergo a much needed defragmentation.

‘Senior Counsel’ (‘for Fali Nariman’) the legendary jurist is personified as precision itself—‘chiseled to perfection’ despite his ‘booming, frail voice’—albeit whispered in a sort of hushed impertinence, adds great depth to Nariman’s personality. This is in accordance with the poet’s philosophy of history, introduced early on in the book, in ‘Turning Points’,—‘I like the kind of history/ That clutches banana flowers at the doorstep.’ History becomes, sometimes, the obverse of the accuracy that the great jurists of the day seek to represent; it becomes lived, felt, tasted as orally rendered recipes, familial structures and admonitions, symbols of quotidian rituals: of ‘the kind of history where father says/ This has not been done before.’ More than a chronology of incidents carved out with a will to sheer methodological accuracy, history is playfully redefined as a space—or a chronotope—through the fusion of a flaneur’s palimpsests with quasi-ethnographic attention to detail, which ultimately resists the dogmas of ‘History’ (with a capital H).

Similarly, ‘The Future of Water’ (‘For Ustad Rashid Khan’), which is one of the emotional pinnacles of the collection, uses the metonym of rains for Khan’s voice—‘You had ample in your hands, just/ Time vast and eternal/ As you held the note in your palm’—whose physical absence in the mortal world makes the poem all the more poignant. Elsewhere, ‘The Day after Durga Puja’ wears melancholy heavily on its sleeves in Goswami’s characteristic bathos: ‘The sun in full autumn brilliance,/ Or a muck-dismantling afternoon.’ For those willing to look past Goswami’s sleight of hand in antinomies and zeugmas, as in ‘We will reach evening by Guwahati’ and Tezpur’s ‘Mahabhairab temple’, ‘mental hospital’, ‘roadside bakeries and fresh cookies’, there lies the tale of waiting for ‘Tathagata.’ However, one suspects Goswami probably intends that too as an anticlimax.

If this reviewer was purported to be one of those serious literary critic attached to modern canonical yardsticks, Goswami’s style might have been called lacking in structural clarity. Since the reviewer is not that, A Different Story reads as a mercifully defiant testament to the promise of a coherent inner village. It does not demand to be interpreted, decoded, anthropologized, advocated for, or politically represented. Rather, it solicits to be inhabited—in one of its quieter rooms where unfirm sunshine trickles into a rotating kaleidoscope containing prisms of childhood, longing, ancestry, displacement, sly laughter, and respectful sorrows. Here poems do not declare. Yet, they beam with the assurance of a lived phenomenology and intuitive perceptions. They constitute a voice that has discovered itself in the repudiation of dogmatic pronouncements and has turned instead to passionate listening.

It would probably be unjust to call A Different Story his magnum opus, even if it is very likely to linger like one in the breath of memory. Although most modern-day critics and proponents of the notion of provinciality will not admit to it, they are bound to be annoyed by Goswami’s book. That is, primarily, because the poet threatens us as being not sad, loud, or radical enough for the standards of a present whose intellectual structures apotheosize illusory ideals of subalternity in collusion with readily marketable entrepreneurial nexuses thriving on the feedstock of human emotions. The poet has watched it all, one can infer, as one of the titles of his poemsruns—‘sitting on a monastery bench watching leaves fall’—while ‘overlooking this theatre of living.’. This reviewer is, thus, deeply convinced of the book’s long future. For, Goswami’s is a rebellious reclamation of the provincial. His ‘words’, as his own prognosis suggests in the final poem—‘tell me a different story’—will ‘live on the broken floor.’ They are like ‘the old train [that] crawls out of its burrow’ while ‘A poet can do very little.’ Goswami rarely pretends to do much as a poet. But he achieves far more effortlessly than those who do so. Had I not known how much he loves Guwahati and New York, I might have been tempted to reconfigure his spaces as Nirad C. Chaudhuri’s Kishoregunj from The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian. But as things stand, his poems are, in the words of Gaston Bachelard, the author of The Poetics of Space, a house that ‘even more than the landscape, is a “psychic state,” and even when reproduced as it appears from the outside, it bespeaks intimacy.’

To purchase this collection, kindly visit paperwall.in/poetrywala/a-different-story/

Arup K. Chatterjee is a Professor at OP Jindal Global University, has held pretigous fellowships in the UK and Denmark, founded the journal Coldnoon: International Journal of Travel Writing & Travelling Cultures, and has authored acclaimed books on Indian railways and the Indian diaspora, besides publishing widely on literature, history, and culture, and the theoretical concept that he has coined and developed as gastromythology. arupkchatterjee.com