This poem was sparked by my own care experience and more recent indirect involvement. The poem itself does not require analysis, beyond what lay behind me writing it.

Two years ago I was invited by Lemn Sissay to be part of a feature in The Observer at the Foundling Museum for ‘achieving’ care-leaders and I rubbed shoulders with the likes of Jeanette Winterson and best of all Sophie Willan. Sophie is the creator of the groundbreaking Alma’s Not Normal and let me have a selfie with her, well two, as I messed up the first one(she’s very patient). Alma’s Not Normal draws on her care background and relationship with her mother, it has won many awards and I heartily recommend it.

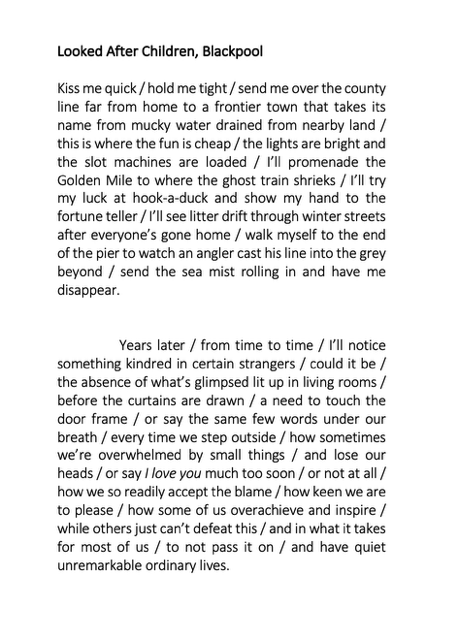

Since being a part of the feature, I’ve been asked to do a few things on care – this being one of them. My own book Whistle about my own care experience was published in 2010 and I thought I had done with the matter. Since the book came out and my show of it toured extensively, Whistle has never really left my life. It is still about a third of my book sales and on the odd occasion I do things for universities, it is always about Whistle. I have published several books since, it is my ‘Streets of London’. 15 years after I finished it, the increased interest in the subject since the Observer feature has found me writing about my childhood again. This includes some poems in my latest book The Remaining Men and this poem which is not really about me, but how things are now for Looked After Children. Anger sparked this poem.

The Care Sector has since my time, become commercialised – there is a profit to be had and for there to be profit, costs must be driven down. This outcome has been vulnerable children, most coming from traumatic circumstances, find themselves being moved to where it is cheapest. The seaside town of Blackpool became the go to place to send them, sometimes many miles from the remnants of their home and any connections there. There is, of course, often resistance from residents close to care facilities.

Blackpool is cheap – why? it has overtaken Glasgow to top the league table for the lowest life expectancy in Britain; a recent study found it has ‘the highest rate of deaths linked to alcohol, drug abuse and suicide in England.‘ . It is therefore the most obvious place to dispatch vulnerable children, by corporations invested in their ‘care’.

Ofsted reported the number of Children’s Homes in Blackpool had quadrupled since 2016. In 2012, Children’s Services in Blackpool were judged “Inadequate” in all categories. In 2014, the service was rated “Requires Improvement”, an improvement. However in 2018, children’s services were again deemed “Inadequate” overall.

It is known that Looked After Children face many challenges, many of them emotional that can lead to anxiety, depression and other problems. At 18 they must leave care and head into an increasingly challenging world for young people. Blackpool is trying to cope with this, but as the statistics show, it faces other challenges.

The commercialisation of care is anything but care. Children with conditions like autism are particularly difficult to place and private companies are exploiting this by charging astronomical fees to provide ‘care’ (which often fails) – to councils who are left with no choice. Vulnerable children have become profit centres, and the costs that arise beyond 18 years of age do not fall on those making the profits.

This was and is allowed to happen. Labour aims to cap profits in the care system. In its 2022 report on the placements market, the Competition and Markets Authority found that, among the largest 15 providers, profit margins averaged 22.6% in residential care and 19.4% in fostering. In the meantime, many children in and leaving care will inevitable and increasingly feed into the mental health system that is already not coping. Care Leavers account for 1% of the population (double that in Blackpool), but around 25% of the general prison population. It is much higher in some areas. This is a cost to wider society as well as the care-leavers themselves. They become a problem and any sympathy from wider society tends to evaporate when they leave care, to be adults.

Children in care do not have much of a voice, they often accept whatever is given and do not dare to speak up, even when given the opportunity. This is in case, however inadequate, their provision might be removed. They feel they need to be grateful for what they’re given, it is surely better than nothing There is an inbuilt insecurity. In care-leaver Ashley John-Baptiste’s TV documentary Care Home Kids: Looking for Love, a 14-year-old girl is already anxious about the cliff edge of leaving care at 18. There are numerous scandals that demonstrate how open to exploitation, sexual, drug gangs etc, they are.

The end of my poem is intended to lay it bare. Yes, some of us succeed, in part due to the survival skills and resilience gained in care, others never get out from under it . The chance to have a ‘quiet unremarkable ordinary life’ should be there for everyone, when it isn’t there, it costs everyone, and many lives are lost way too soon.

I don’t suppose my poem will change a thing, but it won’t exacerbate the problems, which is what we’ve been doing for a long time now.

Martin Figura’s collection and show Whistle were shortlisted for the Ted Hughes Award and won the 2013 Saboteur Award for Best Spoken Word Show. Shed (Gatehouse Press) and Dr Zeeman’s Catastrophe Machine (Cinnamon Press) were both published in 2016. In 2021 he was Salisbury NHS Writer in Residence; the resulting pamphlet My Name is Mercy (Fair Acre Press) won a national NHS award. A second pamphlet from Fair Acre Press Sixteen Sonnets for Care came out in October 2022. His latest collection The Remaining Men has just been published by Cinnamon Press and is shortlisted in The Norfolk Arts Awards. Website: martinfigura.co.uk