Estrangement is a complex, brutal place, both to find yourself in and to inhabit. It’s also a dangerous place to write from, being fraught with exposure, stigma, judgment and misunderstanding; and potentially exhausting, given that in many estrangements there’s no end, no resolution. Yet these characteristics don’t faze or defeat Deborah Harvey in her defiantly-titled collection, ‘Love the Albatross’. She’s a brilliant storyteller, who carries the weight of difficult material expertly.

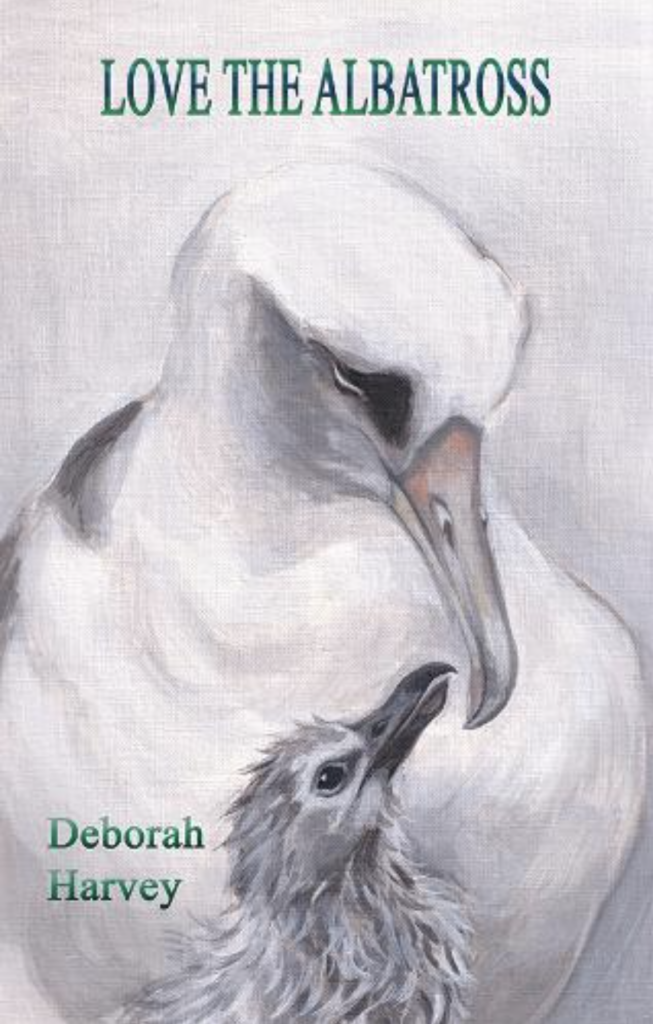

Harvey’s collection explores the theme of loss and multiple estrangements throughdeliberate disconnection, geographical movement and changes in nature. The albatross is a brave and inspired motif for this subject-matter. In the hands of someone less skilled, it could fall flat, but Harvey’s an accomplished poet, with five previous collections to her name, and through her poems the albatross emerges as an emblem of resistance. Like estrangement, it can’t easily be pinned down. In terms of dynamic soaring, she couldn’t have chosen a more apt symbol.

Though in fact, it’s not just albatrosses that wing their way through these poems. Birds, both adults and fledglings, play an important role in the landscape of the text, as messengers and as ghosts. There are also surprising moments of humour: ‘A mother pelican wasn’t something / I’d ever aspired to be’ – shot through with a sudden, starker image: ‘pecking at my breast till it bled’. Not that Harvey is ever heavy-handed: her touch throughout is light, and this makes the loss and displacement all the more heart-breaking when placed in juxtaposition to the natural world. I trust this poet’s engagement with nature. She’s a poet who knows the landscape and exercises a deep

love for it: tender, sharp and extraordinary.

One of the most poignant poems, 51°16’17N 3°1’24W, explores that liminal area of loss and transition:

‘Today I took you to the beach …

… I could see you didn’t really want to be here

but you’ve yet to find a way of evading

the stories that spool through my head, where

walking with me on a winter afternoon can still happen

and all our griefs, all our misunderstandings

lie stranded on mud flats’

while in ‘Just when you get yourself out of one labyrinth’, the prose block form does its job superbly:

‘… trapping your children inside with you where you

can’t keep them safe … stone staircase that tunnels

down, getting narrower with each step… where a serial

killer’s operating by means of secret passages through

cellars … you run through rooms to get to rooms …’

evoking the relentless chasing after meaning, the nightmare horror stories of a constrained desire to be free of searching, to escape.

In ‘Love the Albatross’ there’s no overshadowing, no terminological hierarchy. Estrangement, transformation and albatross are expertly woven together, with Harvey bearing witness to the nuance, complexity and devastation inherent in this most ruinous of losses. As

a reader (and someone who has first-hand experience of estrangement), I found these poems authentic, liberating and transformative. Nothing is more evocative than the feeling that a writer has gone back in time with the reader, as witness and companion. As a result, I’m strangely comforted reading these poems.

It’s these moments of recognition in the context of estrangement that undid me as a reader, taking me straight into the heart of the story, immersed to the point of losing time, not in a dysfunctional, dissociative act of avoidance but in a transformative act of acceptance. The

reader is no longer alone.

However resistant estrangement is to change, these poems break through, shattering the silence that so often holds estrangement in its polarising grip. After the tears it was a relief to settle down with What the currents of the Skagerrak taught me:

‘… but what astonished me then

comforts me now

the convolution of tidal cycles

the push and pull of wind and moon

the notion that nothing we leave behind us

is gone forever.

Resilience, steadfastness, hope and love have never been at the top of the list in my ‘how to manage estrangement’ journal jottings, yet I finished reading this book on a high. Over the last thirty-plus years. I have finally learned new ways of engaging with estrangement that are long overdue.

Love the Albatross is available from Indigo Dreams Publishing for £11.00 plus P&P.

Chaucer Cameron is the author of In an Ideal World I’d Not Be Murdered (Against the Grain). Chaucer’s poetry film collection adapted from her book, is now touring nationally and internationally. She is creator of Wild Whispers poetry film project. www.chaucercameron.com

X: @ChaucerCameron