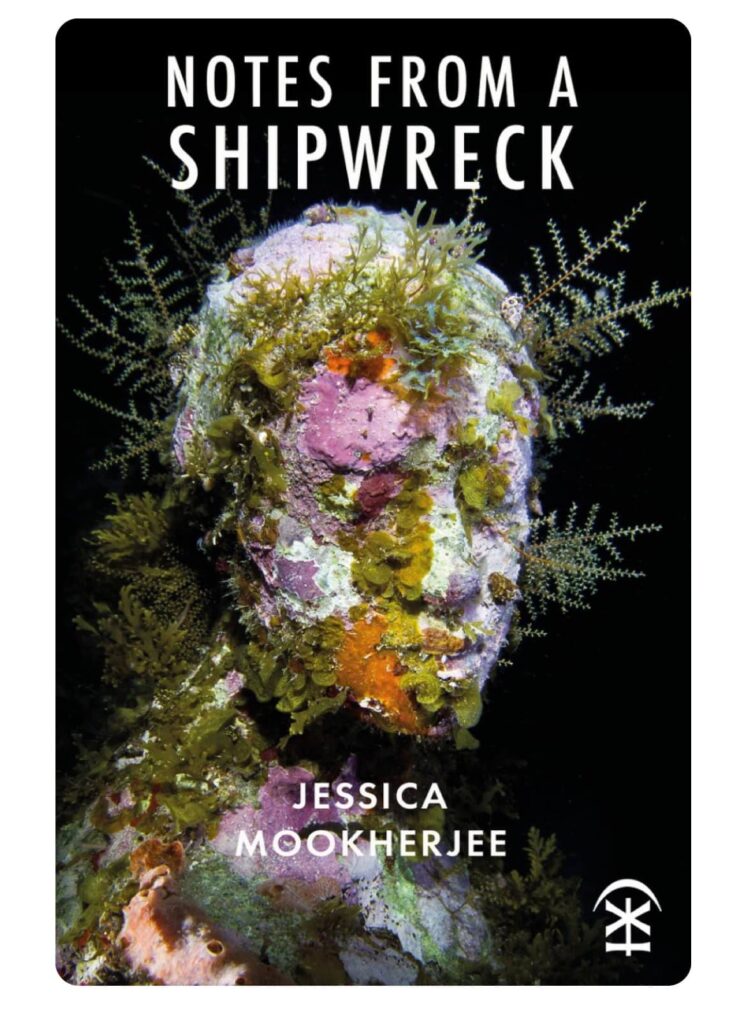

Jessica Mookherjee’s third collection, Notes From A Shipwreck is an epic voyage filled with maritime references. It weaves the poet’s Bengali Hindu heritage with classic European tales and alludes to migrant journeys. The cover image from Jason de Caires Taylor’s undersea sculptures, honours the slaves who were tossed overboard. The gods of the Hooghly and Shakespeare’s Tempest mingle with each turn of her kaleidoscope into a series of colourful mosaics. Jessica has evolved her poetic language to bring past, present, personal and the collective narrative together. Memories of a Welsh, Bengali, Goth girl trying to make sense of it all. Books, pop idols and Krishna images line her bedroom walls. Miranda and Prospero meet Varuna and Shiva. The title poem is set on a whaler near Nantucket, but, ‘the captain, asks me to cook Bengali fish and pray to the Hindu sea god,

Varuna, god of rain.’

She writes:

… I was just a ship-trapped

girl on a rock, far from homeland, it was nothing to do

with me, just a bloody foreigner.

Her family is troubled and her father, ‘calls me Miranda, says I’m his good girl, says my mother/ used me like a doll, discarded, broken and painted blue.’ But Jessica is not a good Brahmin girl, breaking caste taboos by crossing the sea, even though it was just a boat from The Mumbles to Ilfracombe. She gives schoolmates answers they prefer, tells them she’s from India, when she was born in Luton. Mookherjee displays defiance and inventiveness in creating an identity she can live with. She will never be white, neither will she be the good Brahmin daughter. The poet must chart her own route, one that combines Hindu gods, Welsh fish and chips and David Bowie. As an icon, Bowie was a master at reinventing his image: cool, alien, genderfluid and desirable. Goths are like pirates, with piercings and outlaw independence. We ascertain her struggles to relate to a mother whose mind is broken and a father whose values she cannot relate to. In Plague Rounds, she ends:

This is how we spit out our lives and write the lines again,

of how we were first born in the jetsam of burning ships,

wearing signs that say; I’m not my mother, I’m not my mother

and you’re not your father, as we sing: uncurse, uncurse, uncurse.

The poet finds escape once she discovers boys and joins their pirate crew. However, this is not a straightforward narrative, rather a complex work in which autobiographical fragments float like jetsam to mingle with history and fiction. Mookherjee draws on sea voices across continents, centuries and traditions: Hindu, Muslim, Viking and there is even mention of the ‘Unsinkable Molly Brown’ – renowned Titanic survivor. There are non-human identifications such as an albatross and the mythical Harpy, in which she writes, ‘I enjoy regurgitation, dislike the precision of sound, even small noises make me want to tear necks.’

The sea is her context for heritage, colonial history, migration as well as climate change. It is also an archetype for the unconscious and for survival. The voyage we are led on is no pleasure cruise, it is fraught with danger, rage, exile and grief. I don’t pretend to understand all the threads the poet has woven, but their overall effect is one of richness, depth and a sense of humanity. If I have any hesitation, it is simply a wondering whether the poet needed to cast her net quite so wide. Her concept is consistent throughout the book, as Mookherjee reaches a level of understanding and self- knowledge. Dear J, is written as a journal extract in which she refers to an ex-partner:

…I keep a logbook,

only I know about it. I think we can be friends though, so many years

have passed. We are both still alive after all. Like a shipwreck;

covered in sea moss and worms. Alive despite ourselves.

Jessica’s previous collections, Flood and Tiger, are firmly anchored in autobiography, but, Notes From A Shipwreck, aspires to something more universal. An impressive achievement and I look forward to where the poet takes us next.