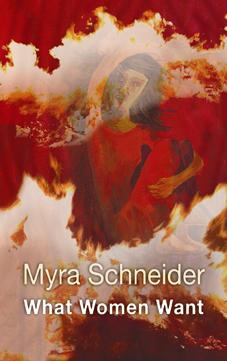

Myra Schneider’s pamphlet What Women Want is full of riches. The poems are textured with images that keep surprising – a chair has ‘a love affair / with mustard yellow’ (‘Le Vieil Homme Assis’); the speaker ‘sift[s] feathers of kindness’ (‘Need’). There is both attention to detail and an engagement with greater concerns. In ‘Copthorne Church’, ’rain [fills] puddle and sea’; the vast, unknowable ‘force which rolls through all things’ shares equal importance with ‘the strange beauty / of mathematics’. Everything, from the object observed to the personal experienced, becomes a part of the life of these poems. They are conversations, between the poet and herself, and between poet and reader.

Myra Schneider’s pamphlet What Women Want is full of riches. The poems are textured with images that keep surprising – a chair has ‘a love affair / with mustard yellow’ (‘Le Vieil Homme Assis’); the speaker ‘sift[s] feathers of kindness’ (‘Need’). There is both attention to detail and an engagement with greater concerns. In ‘Copthorne Church’, ’rain [fills] puddle and sea’; the vast, unknowable ‘force which rolls through all things’ shares equal importance with ‘the strange beauty / of mathematics’. Everything, from the object observed to the personal experienced, becomes a part of the life of these poems. They are conversations, between the poet and herself, and between poet and reader.

An understanding of human nature, in all its forms, underpins the pamphlet. And, more particularly, the existence of suffering, especially that experienced by women. In the poem ‘Woman’ the speaker comes, as suppliant, to a ‘giantess among giant trees’. She is seeking ‘the mothering I’ve always longed for’. Here is the naked self, asking to be clothed. She is offered not comfort but an appalling history of brutality and degradation. Yet it serves its purpose; it takes the speaker out of herself, prompting her to cry, ‘What can I do?’ The reply – ‘”Woman, you have words. Speak, write.”’ – represents a defining moment. While introspection is useful and, at times, necessary, true selfhood is achieved through engaging with, and being in, the wider world.

The transforming power of witness lies at the heart of the long poem ‘Caroline Norton’. Norton’s experience of physical and mental abuse within her marriage led to her intense campaigning about child custody and the conditions of divorce. This determination to translate emotion into action resulted, ultimately, in changes in the law, but at great personal cost. It is clearly a subject the poet feels passionately about, yet the facts of Norton’s life – often shocking – are allowed to speak for themselves. There is a sense of contained anger, disciplined by the use of eight-line stanzas; the repetition of ‘What she did’ (with variation) at the beginning of many of the stanzas reinforces the notion of a determined mind. I found the poem fascinating, and necessary; at its conclusion the focus travels from the past to the present, broadening out into a telling comment on the violence, abuse and misogyny still experienced by women around the world.

Myra Schneider is a humane recorder of suffering and loss. She observes and participates in the hopes and fears of life. The shadow of elegy – for people, past time, childhood – falls across many of the poems; there is a real sense of being present in the past. And yet her outlook, though hard-won, is far from bleak. She refuses an inheritance of ‘bitter dissatisfaction’ (‘Piano’), choosing instead to ‘make sure every day is a finding’ (‘Losing’). There is still joy to be found in this flawed world, gloriously embodied by the two women in the final poem, ‘Women Running’, going forth with a clear eye and an unclouded heart.

Her Story

In the beginning was milky skin

and the warmth of pits – her mother’s.

Later there were oranges in groves and red earth.

The sky wasn’t swathed in clothes,

it unrolled its cornflower-blue as far

as she could see, offered her the sun’s shining eye.

Mother had jet-black eyes

which held the darkness of a well.

Her words were heavier than buckets of water.

She loved her brothers who ran

barelegged down dusty roads.

Often she scampered after them, dipped toes in the river

and picked berries. Freedom

tasted good. It made her

stop her ears to mother’s bitterness, listen to her heart…

Today she is buried

up to her neck in red sand.

Hard eyes surrounded her and hands holding stones.

The blue sky stares down

on her covered head without pity.

It’s too late to start questioning the price of living.

Order your copy of What Women Want, from Second Light Publications here

Zeeba Ansari is a poetry tutor. Her first collection, Love’s Labours, will be published by Pindrop Press in July 2013.