The first thing to be said about Sarah Dobbs’ debut novel is that it does not, in fact, involve killing Daniel. Daniel, the shy deaf boy whose gentle love for Fleur seems, at the outset, to offer her her only hope of redemption, is dead from the get go. Fleur, however, cannot and will not let his memory go, and never does. Arguably, therefore, Daniel is the one person who does not, in some way, die during the course of this uncompromisingly bleak novel.

Killing Daniel tells the stories of three people at crisis points in their lives: Fleur, her former school friend, Chinatsu, and Chinatsu’s husband, Yugi. Each of them harbours a destructive secret and each spends most of the novel teetering on the brink of total disintegration. The action is divided between Tokyo and an unnamed fictional town on the outskirts of Manchester. The characteristics of these settings serve to reinforce the contrast between the material circumstances of Fleur, for most of the novel jobless and living with her grandmother, and Chinatsu who, as the wife of a wealthy Tokyo businessman, has a beautiful home, limitless wardrobe, several servants, and leisure in damaging quantities.

Dobbs casts a cool and forensic eye over relationships between men and women, and does not seem to like what she sees. Though there is sex aplenty in the novel, most of it is loveless and much of it perverted. There is a prevailing sense that men damage women, in obvious ways by treating them with violence and more subtly by suffocating them with overweening economic power. This makes the women, in their turn, incapable of emotional commitment, and so the vicious circle is completed. That this is very often the case is undeniable; one has only to think about certain current news stories to comprehend its prevalence and to feel somewhat downcast by the apparent lack of progress made by feminism.

However, while Dobbs writes powerfully about the potential for destruction in sexual relationships, in vivid, jagged and arresting language, her pessimism is remorseless, with the result that the novel lacks shading. Its mood varies little, though there is some darkly comic relief in the two old wives who offer tough, but practical, counsel to the younger women. Madam Li, a Chinese woman who procures sexual adventures for women trapped in loveless marriages or women who, like Chinatsu, want to become pregnant and have failed to do so with their husbands, quashes Chinatsu’s scruples about infidelity thus: ‘Listen. Women who come to me think they are being whores…No. If you save marriage, it is honourable thing to do.’ Madam Li is old, wise, foul mouthed and has dreadful table manners. She is as practical and unscrupulous as Chinatsu is fastidious and guilt-ridden.

Fleur’s Nan, a joyous crone with her chain-smoked roll-ups, her black and white portable which seems to play nothing but episodes of Columbo, and a tendency to wear socks as gloves, is the one character in this novel who appears capable of loving, though she does this through deeds not words. Her turn of phrase is as blunt and practical as Madam Li’s. ‘Sat here every goddam day, keeping all manner of shit away from you,’ she says, of watching at Fleur’s bedside during one of her hospital stays, and that seems to me to be the most sincerely loving thing anyone says to anyone else in this tale of men and women and the terrible things they do to one another.

As I have already observed, there is a great deal of sex in Killing Daniel, and Dobbs is generally very strong when writing about the physical. Not just sex, but physical violence and its medical consequences are extremely well handled by a writer with an unflinching and unsparing eye for the human body and all its frailties. Her stark and vivid imagery, reinforced by short chapters and jagged rhythms, does not merely describe beatings, illnesses and injuries but forces the reader to experience them alongside her characters, making for an uncomfortable, but authentic, read.

However, while there is much to admire in the novel, in the end, I found its remorseless pessimism wearing. Although there is redemption of sorts for Fleur and Chinatsu, the resolution is sprung on us so abruptly, and narrated so briefly, that it does not really feel like part of the story, more as if it has been tacked on in haste and perhaps against the author’s will. Perhaps, though, this is a misreading, because it is surely significant that both women’s redemption comes in masculine form, which leaves the reader questioning rather than satisfied. Is the circle about to begin again?

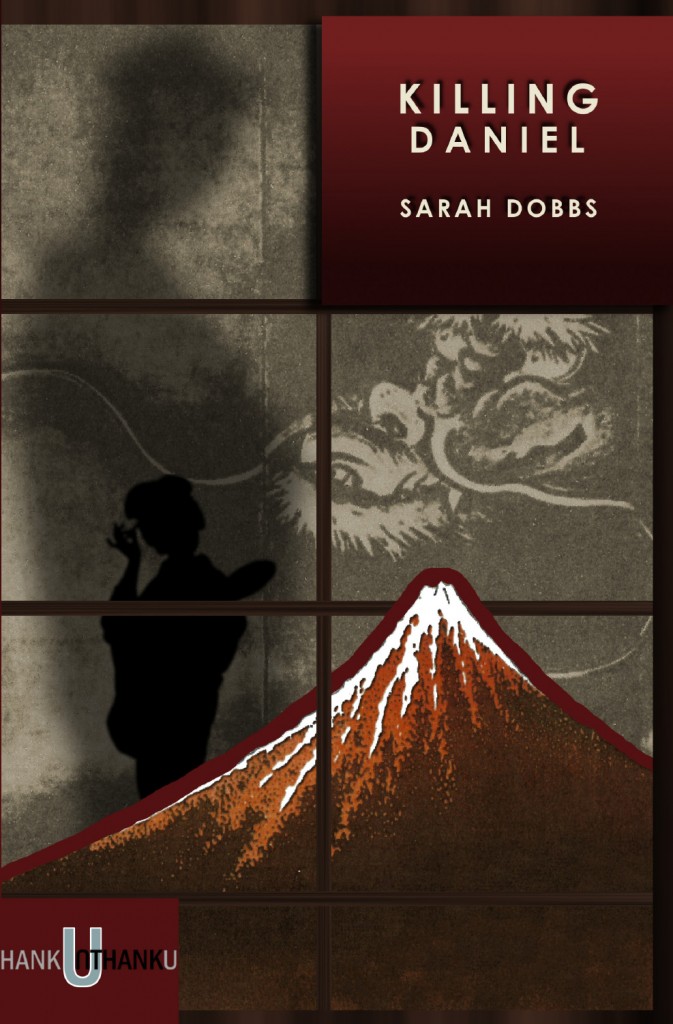

Killing Daniel by Sarah Dobbs is published by Unthank Books. Order your copy here