It should, in the interests of full disclosure, be recorded that this reviewer has been trumpeting the merits of Alan Morrison’s erudite and tendentious verse for over a decade now. Online, in conversation and -once previously, in a book review- Morrison’s flare for words, his passionate espousal of un -or pre- fashionable causes and his intellectual omnivorous-ness have been signposted to anyone who might listen. This, his seventh collection of poems, expands his range still further and treats compellingly of his family’s excoriation by Huntington’s disease -a genetic disorder which rampages through generations, leaving both its immediate victims and their closest intimates harrowed in the cruelest of fashions.

Shadows Waltz Haltingly‘s title-poem takes as its subject the unsteady a-rhythmic gait characteristic of Huntington’s Chorea (which, among its other sobriquets, has been called ‘Saint Vitus’s Dance’).

…the trick with this imbalanced

Balletic feat, this preternatural paso doble,

Tripping quickstep, stuttering foxtrot, rubber-limbed rumba,

Juddering jitterbug, jittery jig, apart from the glide upon

Flat feet, glissades of fallen arches, is in anticipating

Its unpredictability, so that it seems an effortless,

Almost automatic, puppet-like extemporisation

Of motor and cognitive faculties, no strings visible…

The extract quoted above demonstrates typically Morrisonian methods, utilising as it does an ‘impasto’ effect (adapted from the painting technique) by adding layer upon layer of colouration whilst simultaneously incorporating a species of quasi-Joycean word-play (‘Balletic feat… glide upon flat feet’) and Anglo-Saxon alliterative patterning. These syntactically-dense accretions -with their near Word-Association nexuses- can be terribly hard to consistently ‘pull off’, and it says much for their author’s fine-tuned poetic ear that he succeeds far more often than not.

A sizable proportion of this collection stares unflinchingly into this same Huntingtonian neurological abyss (as witnessed in Morrison’s maternal and maternal-grandfather’s case-histories) but nowhere to more effect than in his ‘extended villanelle’, ‘The Rage’. Those of us who have ever attempted that most recalcitrant of poetic forms, the villanelle, know just hard difficult it can be (in T.S.Eliot’s words) to ‘land the kite safely’. Here, with great dexterity and no small craft, the poet assembles sixteen of the constituent word-cages (the usual received number of stanzas is six) with their multiple refrains and limited, binary rhyme-scheme, and still brings them back to earth adroitly.

How does a gentle soul go out in rage?

Most enter in a tantrum, part in tears,

But some -again- rave as they disengage.

{…}

Autopsies thumb the brain’s each cabbaged page,

Leaf flimsy onion skins obscure as smears;

Neurons scoured this gourd, and caused the rage

{…}

No whispered reassurances assuage;

What she grasps abruptly disappears

To shadow’s dislocated mucilage.

{…}

The hunted gene knows few test-volunteers:

Why trace the cureless thunder at this stage;

Pre-empt the protein-pogrom to rampage

Before it has to? Will my punished ears

Prepare me more for when I disengage?

Will augurs fail? Will I go out in rage?

Here is an extraordinary writer at work, perusing the clinical literature, reading-up on his neuro-pathologies, researching his familial prognoses and fashioning what he has learnt into a formally-adept and moving work of art which leaves most ‘un-extended villas’ looking pretty drab and cramped by comparison. This reviewer -a retired nurse who has himself worked with Huntington’s patients- knows of only one other poem in the canon possessing similar stature. In his courageous refusal to surrender to the temptations of despair and his clear-eyed, informed compassion, Morrison has penned his very own ‘Invictus’.

Elsewhere in Shadows Waltz Haltingly we encounter a number of Acrostics concerned with troubled poets such as Thomas Chatterton, Isaac Rosenberg and Ivor Gurney. Several of Morrison’s previous publications have show-cased this form (wherein the first letter of each succeeding line gradually elicits its subject’s name) and he has grown steadily more confident in his range of effects. What is doubly pleasing is the way in which he is now frequently able to assume the featured writer’s idiosyncratic style -as exemplified here by ‘Marigolds to Distraction’ (i.m. Emily Dickinson).

Eyes like the sherry in the Glass the Guest leaves-

My mind is too near itself -cannot see unclouded-

Indian Knots Stich my Heart- Hair like Chestnut Bur-

Leaves me to see into myself -transparently-

Youth Clouding my Mousy Brow -Yellow Buttery.

Miss Emily Dickinson’s daguerreotype holds itself -fleshed out with trademark dashes- up to the cool mirror of introspection.

It would be easy enough to continue to name-check the frequent bright particulars of this stand-out publication (like, for instance, the charming, short formal-piece, ‘Nightbird’) though, unfortunately, too many prized-up poetasters have already left the miniscule poetry-reading public un-bewitched, unbothered (yet) increasingly bewildered. Alan Morrison will, I very much hope, continue to ignite his refulgent verbal fireworks -though it would be particularly sad if they were to merely fizz out into a sparsely-tenanted ocean. Work of this stature -and especially in these challenging times- demands the attention it would so amply reward.

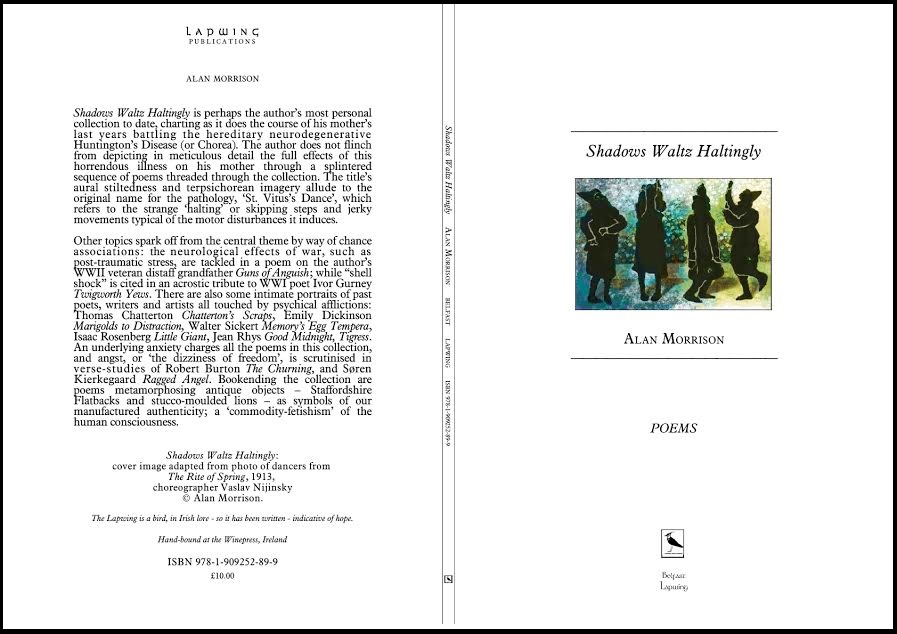

Order your copy of Shadows Waltz Haltingly (lapwing Press) by Alan Morrison, here: lapwingpublications.com/

Kevin Saving is Home-counties based versifier and reviewer in his mid-fifties. His work has been published in ‘Poetry Review’, The Independent on Sunday, The Daily Mail, and (quoted) in The Morning Star. He most frequently writes for ‘The Recusant’ (ezine).