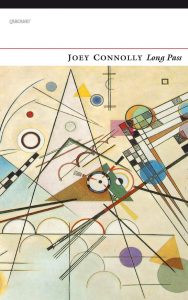

The author of this cerebral and assured debut is the joint editor of a magazine called Kaffeeklatsch. Its manifesto suggests (in the midst of a post-modern welter of interlocking footnotes) that the reader of poetry ‘must be like the cat, flirt with everything’. Long Pass offers a wide variety of attractions up to which the reader may sidle and against which to rub his or her back.

One of the themes of the book is poetry itself and its making, the mutability of the words with which ‘[t]he darkness is swarming’ (‘The Draft’). Connolly is interested in ‘[t]he orthodontic meddling of language/ with the world, its snaggling malocclusions’: ‘[Untititled]’ (sic). At times, his language mimics the sound of nature, as in ‘Liguria’, which captures ‘the plump primary note/ of a woodpigeon swelling rhythmically into the air’:

‘ the glue goes. We pool so, it

schools us. The rules: yes, they fooled you, accruing …’

Demonstrating the scale of its ambition, the collection includes ‘reworkings’ of poems in six European languages. Connolly presents two new versions of each poem (except in the case of Rozhdestvensky’s ‘History’). In each case, the second version departs from the original to a much greater extent than the first. In his second version of Christine de Pizan’s ‘Third Ballad’, which tells the story of the drowned lovers Hero and Leander, the poet addresses de Pizan across the centuries:

‘Listen, Frenchy: the gap between our tongues

is just the blackest water, nothingy and unbreathable’.

The business of reworking is fraught since ‘ideas have words/ and words ideas and they get/ everywhere, sand in sandwiches/ at the beach’: ‘An Ocean,’.

And if poetry and translation weren’t difficult enough, there are also the poet’s ‘financial/ and romantic perplexities’ (‘Why?’), ‘a stack/ of unread books, the constant dull subpoena of alcohol/ and tobacco’ (‘Average Temperature at Surface Level’). An unconsummated love affair is recounted in ‘A Brief Glosa’, having been foreshadowed in earlier poems:

‘Twenty-four days, really, all told,

straggling Manchester’s dive-bars until five for the pretext of drink

between the kitsch and neons as if there was no agony

keeping our bodies apart.’

The poet stands at the edge of a city bridge in ‘I am Positioned’:

‘ thinking of the woman who has asked

for us to keep apart, for two months, while she

works things out: the woman I love. Although

I didn’t, I suppose, make that clear.’

A defining feature of the collection is its willingness to engage with philosophical concepts. For example, ‘to the materialist’, Connolly says, ‘if you can’t ride two horses at once/ you shouldn’t be in the circus’: ‘Of Some Substance, Once’. The book’s centrepiece is ‘Average Temperature at Surface Level’, an extended meditation on information and human attention, and the relationship between seeing, describing and remembering. The ‘tone veers uncontrollably’ from abstraction – ‘object/ bleeds into type, the starvation-ration of quiddity’ – to the helpfully concrete: ‘new, still-wet permanent marker is the best plan/ for erasing old permanent marker’.

Connolly’s work places more demands on the reader than straightforward lyric poetry – e.g. I found myself looking up words such as ‘doxological’, ‘dialetheic’ and ‘ideolected’. Any poetry that is intelligent is in danger of being perceived as overly clever but, for me, Long Pass generally avoided this trap. Admittedly, the line may be crossed in ‘Poem in Which Go I’: ‘There but for the goes of going walks our lord. There/ but for the gauze of saying so goes all’. Another risky moment comes in ‘Fantasy of Manners’, where the poet flagellates himself in Latin for being too intellectual, albeit with deflating mentions of ‘bollocks’ and ‘shite’.

The title of the collection can be linked to the reference, also in ‘Fantasy of Manners’, to the poet’s ‘own hailmary explanatory’ – a ‘Hail Mary’ is a long pass in American football which is unlikely to find a receiver. The pessimism implicit in the title of Long Pass is belied by the excellence of the work it contains. The collection is a substantial achievement, which repays repeated reading. Ultimately, as reflected in his concluding poem, ‘Last Letter from the Frontier’, Connolly’s tenacity wins a strange victory over despair:

‘I know that we have years – perhaps forever – to wait

until the drawling missionaries and the thrill and the skin drums

of pirates. And until then, I am bricking myself in.’

John Mee is a poet and academic from Cork in Ireland. He won the Patrick Kavanagh Award in 2015 and the Fool for Poetry International Chapbook Competition in 2016. His chapbook, From the Extinct, is published by Southword Editions. www.johnmeepoetry.com https://www.munsterlit.ie/Bookstore Other Titles.html Twitter: @JohnMeeLaw