Jacqueline Saphra’s most recent collection with The Emma Press is the result of an inspiring and eye-catching collaboration between the author and award-winning visual artist, Mark Andrew Webber. The successful pair have won the 2015 Saboteur awards for best collaboration and also share the award with composer Benjamin Tassie, who created a soundscape for the poems to produce what Saphra describes as ‘haunting miniatures.’ Grant-funded live performances are underway. Together with the book’s use of the prose poem form (and Saphra is still one of the rare author’s in the UK to use the form exclusively in a collection), this book is travelling and transcending boundaries, gathering increasing recognition in its path.

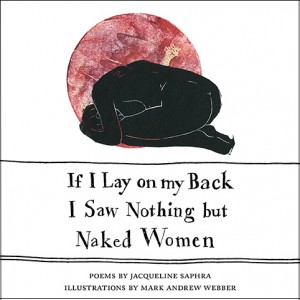

‘Haunting miniatures’ is exactly how I would describe Saphra’s prose poems – their box-like shapes containing the unnerving recollections of a child’s upbringing, told from a child’s perspective, but using a language that moves with eerie fluidity between adult and child. Webber’s linocut of a female figure in a womb-like position on the front cover, a red moon in the background, gets to the heart of the book’s point of view with its clearly lit explorations of power and vulnerability; namely blurred boundaries between the roles of parent and child. The prose poems and accompanying images unfurl like scenes in a play, the author’s background in writing plays for stage and screen apparent here. The atmosphere of the poems is further created by the tension between the tight justified margins of the prose poem’s form and the extremely carefully chosen handful of words to describe the chaos and mess derived naturally from being brought up by a series of parents and step-parents. Their eccentricities are perhaps harmless in public, but less so at home for a child, particularly when home is consistently sacrificed for work:

‘…. Our house was filled

with cookers, stethoscopes, fridges, small

hammers and secretaries taking dictation.

I sat quietly on an ink blotter while

Mother plaited my hair and father

listened to my heart.

The author is perfectly disciplined in her rendition of this hectic and at times disturbing childhood and at no point allows that experience to rattle or over-emotionalise her prose. Humour is also evident, but used wisely and the measured tone of the narrator’s voice and unfussy density of her style (in keeping with the prose poem) is brilliantly pitched against the meetings and clashes between disorder and control throughout her upbringing.

The book is full of strangely tender moments between parent and child, all of which are presented with an almost objective clarity and unemotional distance. Saphra manages to balance the narrative consistently between poignancy and hindsight, most effectively through the choreography of objects and people; their dance is a finely tuned masterpiece of her following them and they being led by her. The objects are used artfully as mouthpieces for what isn’t said:

‘My mother began to throw pots. The

walls of the kitchen were studded with small scraps of clay

… The pots would not shape up… Pouring water at mealtimes

From one of my mother’s jugs became a daily trial of nerve.’

The slips between who is adult and who is child are paramount, particularly when it comes to language; at a dinner party, this betrayal of trust and language is pointedly recalled:

My second stepmother understood about

words. She liked some of mine so much

She often kept the best ones for herself.

Once I caught her pulling a whole string

of them out of her sleeve at a dinner party

but I didn’t let on.

Saphra cuts tirelessly to the quick and the book is full of surprising and unusual examples of such sliding and absent boundaries: a stepmother wanders carpetless corridors during the winter in only gloves and slippers, forgetting herself and answering the door to the postman. In another, her father uses his stethoscope to listen to her mother’s nervous heart and brain, placing the instrument in hot water and telling her ‘to think, think hard.’ In another, the examples become memorably surreal: ‘My mother shrank to the size of a small potted plant….There were no buttons left on our shirts. Dust lay in drifts on the skirting boards; my mother was too small to keep up with the housework.’

Our interest in reading about the language and actions of adults through the experience and point of view of a child is timeless. To have this communicated to us through Saphra’s witty eye for detail and skilled and economical use and understanding of the prose poem’s call for density, clarity and ordinary surrealism is a privilege. To have this further communicated to us through illustration and music is a celebration; poetry is here, healthily talking not only to other poets, but to other disciplines and making the most of them all.

If I Lay on my Back I saw Nothing but Naked Women by Jacqueline Saphra (Emma Press, 2014) is available here