This is a book someone could turn into a Hollywood movie.

Written in a genuinely 60s poetry style, with blocks of indented prosaic lines broken at unusual places and sudden Grand Guignol turns of phrase and compression of language (dropping out definite and indefinite articles), its affectations feel unaffected, of a piece, 60s. As such, it is a triumph of risk, a voice attempted and achieved. One can imagine the 21st century poet Blenkiron, graduate of creative writing, blenching sometimes at his own poetic voice and wondering if he should add in notes, more narrative, more conversational English. One can be grateful he choose not to, and went with the voice.

This is sci-fi poetry, and with voices in it. Sometimes it has the grand phrasing around a simple stark idea of an Arthur C Clarke. Sometimes it feels like a new kind of Crow, with a Hughesian intensity of amoral villainy that also speaks to our selfish inner brat. The world is too crowded, the problems seem immense, the money not there. One sees around one all the short-cuts of road rage, whipped up hysteria against the Scrounger and Immigrant, and the fact that we have a government that is openly attacking and impoverishing sections of the community while semi-passively and even sadistically the majority sits back and does little. As Clarke would do, Blenkiron recasts our present-day world as a dystopia in which the attacking and impoverishing is taken a stage further, in front of citizens’ eyes and still they do nothing to help fellow humans.

Because the fellow humans on the margins are now called, by an incoming demagogue of a Prime Minister, the “Pustoy” (the empty, the soulless). And the Pustoy are being hunted down, murdered in the pages of the poems like the victims of Crow. A dark state, similar to that in Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta, with, again, a Crow-like villain in active madness personally leading the violence with his own self-righteousness, is at work. And people look on, passively, almost enjoying the despair.

And I would pay

through the eyes

if there were a tax on a sleepless night.

I’d have paid with my eyes

not to have seen you taken;

collected like some precious stone from a cave wall,

axed and bagged.

(“PETER MASON”)

The language is rhetorical, and rather like a screenwriter’s in a schlock B movie. One can imagine a hundred creative writing lecturers descending to ask for the language to be made more like everyone else’s poems. But there is something marvellous in the overall project, something Clarkean in the push to tell the narrative, and the lines are more like the metaphor-making of actual people; mixed and gawky. They are therefore much more moving, and the sense is made of a whole culture facing the new government, and everyone reacted pole-axed and a bit dumb-ass.

Phrases pop up throughout the book that bring a John Berryman, almost Olson, clump of descriptive intensity, coming close to exaggeration and dissonance, an overplus of possible ideas and puns just plonked there.

I wonder, unwound toy,

if they buried your turn-key

somewhere near you.

(“UNWOUND”)

dense rock pours

moonlight

clam spit and grit

turn pearl

(“STILL THURSDAY”)

And sometimes this rises to a more controlled Peter Reading like, and less flailing, cold savagery: And eager to please their masters,

eager to learn, bull-headed beasties trot beside them.

Their hearts of gold, tarnished, only slightly,

by the throats they carry in their mouths.

(“OPERATION STAFFHOUND”)

But, note, this is the end of a poem in which actual people have become like dogs, and then the people-dogs have actual-dogs to accompany them; and this is told in a prosaic lollopping style “only slightly” rather than as Reading would have done all in fragments, all milled and jagged. “Throats they carry in their mouths” is the single great poetic line I’ll take from reading this book.

It’s a very unusual book, and it feels as if it pushes stylistically against the accepted styles of our age. It doesn’t do this by backward-looking retreat into the marbled style of any one of this generation’s forebears. Instead, it pushes forward with a story to tell, a cast of characters (often caricatures, but in the sense of Punch and Judy not of ineptitude). Its images last with one, and its world, and I could see it taken forward for screenplay adaptation, whole lines of dialogue and the overall set-up and the movement from poem to poem seamlessly transferring over. I wouldn’t especially want to go back and read the whole book again, nor would I signal out one poem to show to a student. I would say, read the book, get challenged about what style you’re using, and challenged about the casual violence of the modern clean-up squads of modern governments. As an outcome of reading a book, that’s not a bad result.

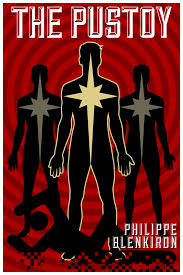

Order your copy of The Pustoy by Philippe Blenkiron, published by Dagda Publishing here