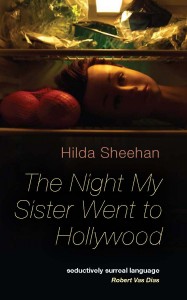

The Night My Sister Went to Hollywood is a debut collection from Hilda Sheehan, a mother of five who is the editor of Domestic Cherry magazine and works for Swindon Artswords. To judge from this collection, she is also an accomplished and idiosyncratic poet. Bristling with the stuff of everyday life, her poems are shot through with dark humour and surreal insights. The collection is divided into two sections. In the first she defines and explores her territory, a world in which, like the young mums in Larkin’s ‘Afternoons’, ‘something is pushing’ her protagonists ‘to the side of their own lives.’ Although this is an area which has frequently been visited by others, Sheehan brings to it her own slant, exploring various dichotomies: the banal and the miraculous, the mundane and the seemingly glamorous, the explicable and the disconcertingly surreal. In the second section the same polarities are at play, but her eye is focused more particularly on the conflict between romantic love and the pressures we all find ourselves under in coping with the business of life. In her title poem Sheehan explores quotidian reality against the backdrop of the movies:

she left a stare on the bathroom window

and rubber gloves slumped over taps

like yellow dresses waiting for a clean.

However, there is more than a hint that our longing to escape may also be a form of posturing and self-indulgence:

Hollywood made a film with most of the crying

included, ending with the hope of highlights,

Botox, bigger lips and no one seemed to care

if her bed was made, if her bed was unmade.

In ‘Not in the Stars’ she exploits again the image of Hollywood in a brilliantly concentrated narrative:

I was never a Vivien Leigh

but we rode the same streetcar once:

her on her way to torment,

me on the way back.

In this wittily textured poem Sheehan draws an effective contrast between Vivien Leigh in her portrayal of the self-dramatizing Blanche DuBois and a second more down to earth protagonist who seems nonetheless exhilarated at the spectacle of another’s life in meltdown: ‘… she got off, bright as a naked light bulb, / left me in the empty streetcar / to throb with exciting life.’ In ‘Don’t Tell Louise’ the poet again plays brilliantly with dramatic voicings. Hitching a lift with a man who claims to be Jesus, Louise is unimpressed and sceptical: ‘he’s fake: no one can walk on water, / no one can rise from the dead.’ However, the second unnamed protagonist seems more open to the possibility of miracles: ‘But I’m not so sure, Jesus is perfectly nice, // he offers us eternal life.’

In ‘Tragedy from a Bathtub’ Sheehan moves away from the glitzy fables of Hollywood and deploys some of the characters of Shakespearean tragedy to evoke the breakdown of a dysfunctional family:

When mother awoke

she tackled the washing up

but found life too dull without Romeo

and left, through a door

I could never find in the cellar.

Elsewhere, as in ‘Oh Asda!’, she widens her net and moves from the narrow locus of the bathtub and kitchen sink to a broader consideration of social mores and the world we are creating for our children: ‘We feed our young expired values, / left cold in the fridge for days – / look closer: see the vulgar stamps / on eggs, our toxic guilty plastics.’

Like any good poet, Sheehan explores a reality she knows. In ‘Kitchen Drama’ she convincingly evokes the domestic drudgery experienced by many working mothers: ‘So many women in one kitchen: / cleaning the sides, scrubbing the oven.’ However, in ‘The Golden Lampstand’ she explores her aspirations as a woman and a writer in more explicitly feminist terms. Inspired, perhaps, by the playlets of Kenneth Koch, a writer whom she clearly admires, the poem is written as a dramatic fragment in which a woman is visited by a group of men who lay claim, on behalf of God, to the eponymous lampstand. The woman’s reply is defiant: ‘God will have to wait. / I am writing a poem and I need the light / of that particular lamp.’ I suspect, however, that Sheehan is too talented a writer and too wise to let herself become over- programmatic or to see things too clearly in black and white.

In the second half of the book she focuses her attention on the relations between the sexes. ‘Stuffing’ is a poignant evocation of teenage love: ‘… whispering goodnight / to a slammed door, then kicking / pebbles home, singing Love Action, / wishing we were older.’ In ‘The Long Walk Home’ the idea of glamorous escape is debunked by a catalogue of names that are much nearer home than Hollywood: ‘He wanted to take me away to Leicester, / Grimsby, Preston; take my pick, decide later… // Instead, I got off home, did the kids’ tea;’ while in ‘Your Eyes Are Nearly Your Best Feature’ her deadpan humour creates something like a parody of a poem by Donne:

… your belly is like East Anglia;

I can see all the way down long legs out to sea.

Your breasts: the Pennines, or should I say Peaks?

Papplewick Pump Station!

However, amongst these brilliantly ironic love poems ‘Various Things’ would perhaps be my personal favourite:

I love you, I do. It’s just that,

time is running out, it’s Sunday. Asda will shut soon…

Remember Holborn? When you kissed me,

a train stopped and let more people on

I love the red bits in your hair.

Shall we dust?

If you move next door, we could pretend to be lovers.

When you get back, we could put up a shelf.’

The Night My Sister Went to Hollywood is a fully achieved debut in which the poet subverts the details of routine reality to create a world that is uniquely her own. It is a place where a seal can mysteriously appear in your bathtub, where a woman in despair becomes addicted to ice and starts hallucinating, or two lovers share a bath and try to converse in a mixture of English and Serbian. Many of Sheehan’s poems have an immediate comic appeal but manage also to articulate stoicism, frustration, tragedy and longing. They have much to tell us about who we are and the times we live in.

Order your cop of Hilda Sheehan’s The Night My Sister Went to Hollywood from Cultured Llama Press, 2013 here