The term ekphrasis and its relationship with poetry is one which troubles me. The word finds its roots in Greek; ek meaning ‘out’, and phrasis ‘speak’. The general understanding of this concept being that the work of visual art is spoken out on to the page, dramatically translated into written form. Before mass communication made it possible for us to see a work of art without actually being in its presence physically, one function of ekphrasis was presumably to ‘show’ us works of art in lieu of a reproduction. In the Google-age the poet’s engagement with the visual work of art must go beyond description. In House of the Deaf man Andrea Porter and Tom de Freston employ an intriguing mode of ekphrasis, giving a voice to fourteen of Francisco Goya’s paintings in a delightfully perverse act of ventriloquism.

Goya moved into Quinta del Sordo, the house of the deaf man, in 1819 and over a period of five years completed a series of works which would become known as the Black Paintings. By this point not only was he completely deaf, but beginning to lose his sight as well. The conversation that occurs in House of the Deaf Man then, is between three artists. The first cannot see, hear or speak for himself. He is instead spoken-out by Porter in a series of poems which restage these private works (the Black Paintings were painted directly on to the walls of Goya’s country house and never intended to be shown publicly) in contemporary Britain. One poem ‘Pap’, is dedicated to Rupert Murdoch and gives a voice to the two figures in Two Old Men Eating Soup

We like soup, it slips down easy,

saves us gumming away at stuff

that will never break down

to something we can swallow.

This gentle juxtaposition is typical of Porter’s understated humour and gentle satire. Here we are moved beyond ekphrasis-simple to something very subtle indeed, the evocation of Murdoch’s tabloid empire, the eroticism and violence of these publications juxtaposed with Goya’s skilful and anguished application of these themes.

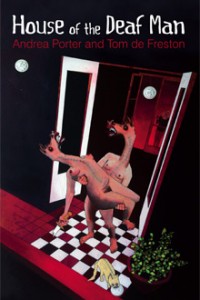

The third speaker in this conversation, de Freston, answers the questions raised in Porter’s poems with further questions. In contrast to the epigram to ‘Negative Space’, a quote from Goya which states that for him there are ‘only forms that are lit up and forms that are not… only light and shadow’, de Freston’s illustrations employ hard ruled lines and skewed geometries, making little use of shading and where he does this is achieved with cross-hatching. The majority of these responses are claustrophobic dioramas, the rooms of the House of the Deaf Man are exploded on one side so that we can see in.

One motif which occurs in several of these images is a body from the neck down descending a staircase, emphasising the voyeurism one must feel in the face of Goya’s intimate paintings. We feel as though we are constantly walking in on something in Porter’s poems too; the narrative perspective shifts from poem to poem which can be jarring. Continuity is instead provided by themes of sex, violence and domesticity. As such, we may surmise that the mode of ekphrasis employed is one in which several voices speak over the top of each other; each responding with their own stories, told in their own idiom. A mode which is coherent, but only just, manically, and on its own terms.

House of the Deaf Man: poems by Andrea Porter, illustrations by Tom de Freston, 2012, Gatehouse Press 56pp | £10 Buy your copy here