It is difficult to write about big subjects without recourse to the abstract, and so Wendy Pratt’s first full collection is especially impressive given that its overwhelming interest is death. Pratt eschews abstraction first by rejecting mere ideas or notions as germs for poems, and secondly by refusing to remove – to abstract – differing modes of experience from the whole. All is of a piece. The mind, for example – distinctly abstract – gives way to the skull, as in “the skulls of students” (‘After the Digging is Done’) being filled with books and lectures about the mesolithic lake people of Starr Car.

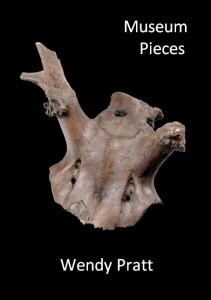

Had I been the editor of this book I may well have insisted on calling it ‘Bones’, for the bone is a recurring symbol that seems to unite these poems. There are cheek bones, vole skulls, thigh bones, horse bones, vertebrae, deer skulls, bones of trees, little bones, bones of this and bones of that, even a whalebone corset – suggesting linkage, permanence, connection, strength, timelessness. The past inhabits the present in Wendy Pratt’s world – it “smoulders” (‘A64’) as peat smoulders.

The poet populates the quotidian with the mythic, conflates the inside with the outside –there is no Cartesian distinction as between body and mind: they are one. Words too inhabit the same intensely physical world: they “tangle / in the strawberries and weeds” (‘First Words’). Pratt promotes a kind of modern pantheism, in which everything is connected. In ‘Jesus of Nazareth Walks on Water’ the god “walks / to the boat, rests a human hand upon the wood”; in ‘Horse Singing’ “a universe can exist / in the dull thump / of a hoof”.

Nor is it only the human that is given personhood: wine “scampered / up and down my veins” (‘Driving Dangerously’), there is an ode to a polythene bag – “we’ve shared / our half-truths, bag” (‘Bag’), the poet’s mother’s bicycle is “No longer plagued by the intense futility / of age” (‘Black Beauty’); the landscape has “vertebrae” (‘Over Saddleworth Moor’). It isn’t a one way process: people are given planthood. They “intertwine / like tree roots” (‘It is Only Lunch’), wrists link like vines (‘The First Mrs Rochester’), the poet herself becomes “driftwood” (‘Raven Hall’).

Wendy Pratt gives life to everything, even as death undoes everything, including the poet’s child. The most moving poems in this collection are in a section entitled ‘The Unused Room’, and I hesitate to write about them, except to say that sad as they are, Wendy Pratt has succeeded in giving meaning to a life hardly lived. And even in these poems the felt is more important than the thought. In ‘The Blessing’ the childless mother feels “despair / balling up like a piece of stale bread / in my throat”. The mundanity of the image is shocking, but what it achieves is immediate connection. The reader is forced into the scene. I think this is very good poetry.

Museum Pieces is full of ghosts and hauntings (and a witch, the poems about which I have reviewed elsewhere – see Nan Hardwicke <http://www.wynnwheldon.com/search/label/Wendy%20Pratt> ), and, as poetry is perhaps haunted to some degree by Ted Hughes, another poet for whom the sacred and the mundane inhabited the same space, for whom the imagination was a tool not a toy.

Much of contemporary poetry is mere reflection, gobbets of prose in effect. Wendy Pratt does something only proper poetry can do: to make associations and connections across acres of symbol and image and idea, to address the most common of all subjects, death, provoking not only thought but also feeling. Fiction lures us into another world, but Pratt’s poetry invites us to explore our own, not factually, in the way of prose, but by way of the imagination. She is, in this sense, a kind of Coleridgean romantic. These ‘museum pieces’ are anything but. Death may be Wendy Pratt’s great subject, but her poetry throbs with “the rhythm of blood”, turning lived experience into vivid art.

In order for this not to sound like the rantings of a Prattitioner, I would add that I think the collection might have done with a little editing, and I am not sure it needed to be divided into sections (there are seven in all). Two of these sections, namely ‘A Box of Teeth and Claws’ and ‘The Cabinet of Hearts’ might have been excised completely, not because their poems are inadequate but because they are not quite so thematically coherent. Having said that, there is one poem, about love and death, which elicited from this reader a gulping sob at its last phrase, and deserves anthologizing by whomsoever compiles the next book of love poems. It is called ‘Shoe Trap’, and it is loving, as all Wendy Pratt’s poems seem to be, in a very particular, robust and inimitable way.

Star Carr

Flint arrow heads spilled like lost teeth,

found again, drawn up through the black

peat. They surfaced so often against

the shear side of a spade or beneath

the soft sole of a Wellington boot,

that they became common: a currency

in the playground; pocketed

with leaf skeletons and vole skulls;

our own histories marked out

along the chipped edges. And later,

at the official dig, deer skull hunting-masks

rose from the forgotten lake bed.

Glimpsed through the billow

of a white plastic tent they eyed us

with unwitting curiosity, watching

the new world; their faceless mouths

un-stoppered.

Shoe Trap

In the dark I grope across the bedroom

floor, feel for the shape of the wall, the door

and half trip, half step over your work shoes.

Shoe trap. Your favourite trick, four

shoes, haphazardly strewn,

your habit. My habit is the stumble, the meeting

of floor and face, the standard bruise

to the knee. Your shoe trap has held me captive

for thirteen years, swearing in the dark on my way

to the bathroom. Your habits and mine; a dance,

a meeting of selves over and over. The day

after my sister loses her husband to cancer,

I trip on your shoes in the dark, holding their scrubby,

battered shape, I’ve never felt so blessed or lucky.

Museum Pieces by Wendy Pratt is published by Prolebooks, 85pp, £6.50. Order your copy here.