A Poet’s Journey of Abandonment, Near-Death – and Recovery.

This is a second collection of poems by the Iowa-born poet who has lived in St. Paul the last three decades or so. Not just living, it must be emphasized, but surviving ordeals – the collapse of her marriage, her brain surgery to remove a tumor the “size of a baseball” and then learning basics all over again – speaking, walking, driving a motor vehicle, the fundamentals of resuming life as a functioning woman in her late fifties, but always with the filling reservoir of language and poems, her gratitude and astonishment to be still alive.

The central motif of this new collection is putatively “Odessa” – but not the city port at the Black Sea or the town in Texas. Instead, it refers to a small town about three hours west of Minneapolis near the South Dakota border. If one can gauge the chronology accurately, the poet’s visit took place before her medical crisis (actually the dominant theme here). Kirkpatrick’s gift is in her succinct language and bare yet full imagery. Here are central lines from the title poem:

I am always afraid of what might show up, suddenly.

What might hide.

At dusk I saw the start of low plateaus, plains

really, even when planted. Almost to the Dakota border

I was struck by the isolation and abiding loneliness

yet somehow thrilled. Alone. Hardly another car on the road

and in town, just a few teenagers

wearing high-school sweatshirts, walking and laughing, on the edge

of a world they don’t know.

Darkness started in as heaviness in the colors

of fields, a tractor, cornstalks, stone.

Kirkpatrick’s first book, Century’s Road, appeared in 2004 and was well received but not widely reviewed. She was over fifty, but at least had her first book published, and began looking at her life’s interstices for a second volume. Now a poetry teacher and professor, but not having arrived at poetry until her senior year at the University of Iowa, Kirkpatrick later went through divorce while her two children were not quite on their own. Still, the functions of termination had to be endured, recounted in a sequence titled “The Italo Poems” and borne without rancor in “The Attorney” – as these opening lines attest:

Your husband is leaving.

You have to choose.

You have to get an attorney.

Go downtown near the steeple and the derelict pigeons

where the bells alone cost millions.

Walk into corporate heights, crying,

state your name at the desk,

weep at a table longer than your dining room,

decide what to keep and give up.

Smart and tough

without love, the attorney

knows the law, knows the patterns . . .

How should one quantify bad luck, or what seems like it at the time? In this book, Kirkpatrick prefers to convert negativity into poems marking her journey’s byways – medical, physical, and emotional. She displays no interest in vengeance or score settling.

What came next, of course, was her brain tumor, recounted first in a thirteen-page sequence of synchronous yet restrained verse both mellifluous and stark. Indeed, “Brain Tumor” is a tumbling but focused recalling of her precipitous dance with mortality: “You stumble because your brain has been pressed / for so long, its tissue is damaged, its current volcanic. // Now you understand the numbed foot, / the jumps, floaters, and tingling. / Now you are seized and perpetually falling . . . .”

The remarkable aspects of this collection resound in the witnessing Kirkpatrick does of herself, those around her, her efforts in recovery, doing her therapy as prescribed, good days and bad, persistence a recurring theme. In an eight-sonnet array, “Time of the Flowers,” she records her observations and includes tiny phrases from contemporary writers (e. g., Carolyn Forché, Paul Gruchow, Laurie Scheck, Peter Sacks, Carol Bly, and others) at the bottom of the pages instead at the top near the title. This leads the reader to concentrate on the poem first, not so much a quote from someone else. Still, these sonnets also weave allusions to Greek mythology, Native American literature, and other voices preceding her lifetime. Her themes flow seamlessly, the images both independent but merging into each other, as in the second sonnet, “Survivor’s Guilt”:

How I’ve changed may not be apparent.

I limp. Read and write, make tea, boiling water

as I practiced in rehab. Sometimes, like fire,

a task overwhelms me. I cry for days, shriek

when the phone rings. Like a page pulled from flame,

I’m singed but intact: I don’t burn the house down.

Later, cleared to drive, I did outpatient rehab. Others

lost legs or clutched withered minds in their hands.

A man who can’t speak recognized me

and held up his finger, meaning “one year since

your surgery.” Mine. Sixteen since his. Guadalupe

wishes daily to be the one before. Nobody

is that. Like love, the neurons can cross fire.

You don’t get everything back.

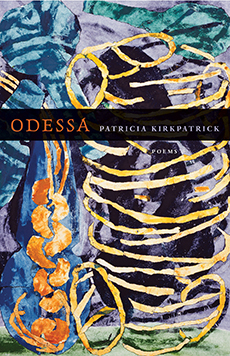

No, perhaps not, but the poet still has her tools at the ready. This book, most of which was written after Patricia Kirkpatrick’s brain surgery, is testament to the gifts she has always had. Odessa has numerous and recurring themes, metaphors and allusions weaving in and out in surprising ways – the small town with a famous name she visited on the prairie, her personal losses, her desperate but successful efforts at keeping rational perspective when her life was in serious jeopardy, going beyond that to make poems, to reclaim her life and keep on. In so doing, Odessa is a gift to us all.

Odessa by Patricia Kirkpatrick is published by Milkweed Editions. Order your copy here.