There are fifty-two complex, thought-provoking poems in this, Angela France’s fascinating third collection, all of them engaged with what are clearly deep, lastingly cental preoccupations and, despite her view in “Anagnorisis” that “My only surety is carbon and water, ashes; / language as sensation, / no words”, more than justifying the fulsome back-cover endorsements of Nigel McLoughlin, Deryn Rees-Jones and David Morley, who speak of the “integrity, thoughtfulness and care of her work”, its “uncanny command of language and image”, the sensitivity with which she perceives the world “as she searches for meaning in the ordinary” and its “gloriously sheared weight and shared music”.

Early in the collection, her relationship with a grandmother figure and thereby with older women generally, becomes the path via which she investigates, with great intensity, her premise that “Men don’t tend the fire; … They don’t make old bones” (“The Evolution Of Insomnia”), whereas, as she says in “Canzone: Cunning”, life gives women ever greater power and wisdom as they age: “You always knew what you were, old woman. / I grew knowing the wink of your cunning, / the cackle and knock of a comfortable woman / who had aged past appearances”. Women, it would seem, learn more with the passing of the years about themselves and survival than do men. It’s a recurrent point about staying-power, made again in “The Visit”, for example, where “an old man leans from a narrow bed and the colours of dying / are yellow and white. A sheet winds round him, rumples / to leave a scrawny leg exposed” and in “Counting The Cunning Ways”, a poem in which an unidentified male figure, a grandfather perhaps, preoccupied all his life with an armoury of superstitious nostrums designed to keep misfortune and death at bay, “so many ways to foretell death and disaster”, such as taking “a long way round / to avoid meeting a hearse head-on”, not taking “the ashes out after sundown” and refusing to “wear anything new to a funeral”, discovered at the end that death “came for him while he wasn’t looking.”

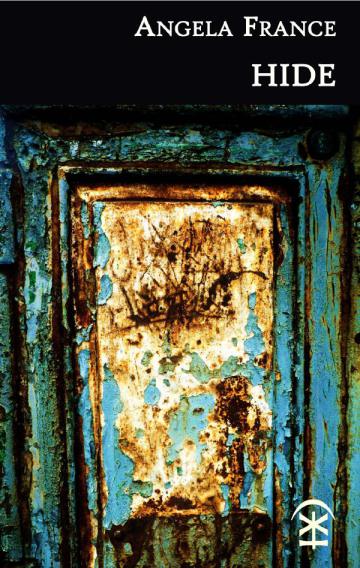

By way of contrast, France’s unremittingly scalpel-sharp analysis of her relationship with the world suggests profound, perhaps lifelong, insecurities. In “Getting Here From There”, for instance, she speaks of her need to “name where I tread / grass, rock, mud / to fix the ground beneath me” as if she doubts, not merely philosophically but physically, the reliability or permanence of the world’s surface, whilst in “Hide”, the poem which gives the collection its title, she writes about her need for concealment, disguise, hiding-places within which she can “wait out seasons for a day / when clouds bloom into stories … / watch swifts skirl overhead, oblivious / to my hungry eye”. “I have always craved secret places:” she says, “rooms within walls, smugglers’ tunnels, / the bookcase that glides sideways / for a knowing touch”. It’s a perception of herself that goes back, she tells us in “Spy”, to childhood, when she “moved among” other children “to learn their playground games / and language,” but felt that at least some of the boys were convinced that “she’s mad, she is, / talks to herself all day!”

There’s a great deal more to be said about this aspect of the poems, the extent to which thinking about one’s life is a task never completed, the struggle between feelings of belonging and alienation, the need to be oneself and yet not be alone, than can be said here. In “How To Make Paper Flowers”, for example, she speaks of learning to “Bury the memories of your grandmother” and of not thinking of “your grandfather’s chrysanthemums, cradled in newspaper / and tied to his bike’s handlebars / as he rattles home from the allotment / or the daisy-chain you hung / round your father’s neck.”. These are fine lines, simple, universal images of remembered loss, of deep affection. “Sam Browne” works similarly as she remembers her father using Brasso, pungent, once smelled never forgotten, “a metal tang in the throat”, to polish metal uniform buttons and in a single, very moving line captures the ache of the loss of a parent: “I breathe my dad as he straightens his cap over his eyes.”

The frequency of France’s use of the word “cunning” and words related to it suggests that it is a key to the collection. Its etymology, from the Old Norse “kunnandi”, “knowledge” and the Anglo-Saxon “cunnan”, “to know”, is many-layered. Associated with it is the word “canny”, knowingness, craftiness. Equally, it suggests wit and wisdom, learning and erudition, as well as skill in the occult, deceitfulness, evasiveness and selfish cleverness. The Canadian novelist Robertson Davies wrote a novel entitled “The Cunning Man” which is concerned, among other things, with shamanic and mystical power, whilst among the fallen angels in Book Two of John Milton’s “Paradise Lost”, there is no better term than “cunning” to describe Belial, whose words were “false and hollow” and who, “though his Tongue / Dropd Manna, could make the worse appear / The better reason” … /for his thoughts were low …”. As France uses it, “cunning” is a word rich in ambiguity, a double-edged sword sometimes, perhaps, but always an indicator of the degree of her engagement with the challenge, as “Other Tongues” makes clear, of coming as close as possible to the inexpressible heart of the matter: “When I say I’m alone, I’m lying. / My mother tongue sleeps under my skin, / bred in the bone, colouring my blood. / I speak from an echo chamber / where the walls pulse with whispers, / familiar cadences rising and falling / at my back. I speak from a limestone floor, / as familiar to my feet as are the bones / of the hill creaking between the roots / of great beeches. I speak with multitudes / in my throat, their round vowels / vibrating in my stomach, their pitch / and tone stiffening my spine.”

Order your copy of Hide by Angela France from www.ninearchespress.com

©2013: Ken Head www.kenhead.co.uk