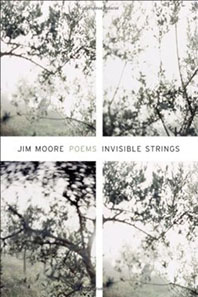

This delicately rendered collection has many durable insights conveyed simply, almost epigrammatically. These poems have clarity as well as many saddening, irrefutable truths, a mixture of both prose as poetry and poetry as prose, although the dominant genre is poetry. This is Jim Moore’s sixth collection. His first book, The New Body (Pittsburgh, 1975), appeared when he was thirty-two.

This delicately rendered collection has many durable insights conveyed simply, almost epigrammatically. These poems have clarity as well as many saddening, irrefutable truths, a mixture of both prose as poetry and poetry as prose, although the dominant genre is poetry. This is Jim Moore’s sixth collection. His first book, The New Body (Pittsburgh, 1975), appeared when he was thirty-two.

Full disclosure: I am a mere three months younger than this poet, so when he writes about the near-despair of aging, his own or those he sees in his beloved Saint Paul or in Spoleto (his adopted home in Italy), his insights have an unstoppable truth-telling (as Richard Wilbur once described Ruth Stone’s poems). The deaths of one’s parents, for instance, and later remembering them beset the poet, as in the opening part of “Love In The Ruins”:

I remember my mother toward the end,

folding the tablecloth after dinner

so carefully,

as if it were the flag

of a country that no longer existed,

but once had ruled the world.

Or later in the fourth part of the poem, whence the book’s title, there is a sentient theme that if the poet keeps busy at his craft, he will live and not have to die any time soon:

I vow to write five poems today,

look down and see a crow

rising into thick snow on 5th Avenue

as if pulled by invisible strings

and already

there is only one to go.

The brief portrayal has always been a hallmark of Moore’s work ever since he began publishing his poems more than four decades ago. As such, Invisible Strings has many short though complementary parts, rendered into mellifluous sequences. In this vein, too, the poet has always been aware of injustices. Earlier in his career, he might have thought as a writer he could do something about inequities and wartime killing. Boris Pasternak’s admonition here is worth recalling: a poet, or any artist, must witness, describe what is seen. But to do more than this is to risk bitter disillusionment, even premature death. Moore serves as an eloquent witness. He may be in Saint Paul or Spoleto, but he’s fully aware of starkness and unbidden death elsewhere, as in “Poem Without An Ending”:

Listening to acorns fall

such a lovely sound

I thought it was the whole poem

until I saw the girl in the paper

with the mussed hair

the bombed bus

no one bothering yet

to close those two black eyes

For anyone who has experienced rejection after a long relationship, the memories can be poignant, lasting a lifetime. The following short poem, punctuation in the title, will allow perspective – maybe:

TRUE ENOUGH,

I have forgotten many things.

but I do remember

the bank of clover along the freeway

we were passing thirty years ago

when someone I loved made clear to me

it was over.

Rather than unremitting bleakness, Moore’s poems can also display wry insight and subtle humor. This volume is dedicated to his wife, the photographer JoAnn Verburg, hence the book’s epigram to her, and what a milestone means, as in the third section of “Anniversary”:

One bird, then another

begins to sing

outside the store

where you try on dresses.

The black is beautiful,

But so, too, is the blue.

To find love again after disappointment is always good. Moore can still recognize irony in one sentence toward the end of a long prose-poem titled “My Swallows Again” – written in Spoleto: “How can you not love a country where the meter maids wear high heels?” Except for this longer effort at the book’s end, Moore indents every other line in these poems, as if to slow down one’s reading, as Renee Emerson has suggested. Variance in poetic strategy is always a risk, but the reader does stop and think, even reread – and this has a salubrious effect.

Invisible Strings is a book of strengths, evoking the onrush of getting older – it’s always a rude awareness – and having to say good-bye to those one cherishes along the byways of mortality. Born in mid-1943, Jim Moore should have many poems and collections of this high quality still to come.

Invisible Strings was published by Graywolf Press in 2011. Order your copy here