Chagall’s Circus is set out in five sections with poems alternating between pristine tercets that give each stanza room to breathe, and relatively short blocks of text in contrast. Poems are headed by quotations from Chagall’s autobiography ‘My Life’ (1923), and facilitate the storytelling.

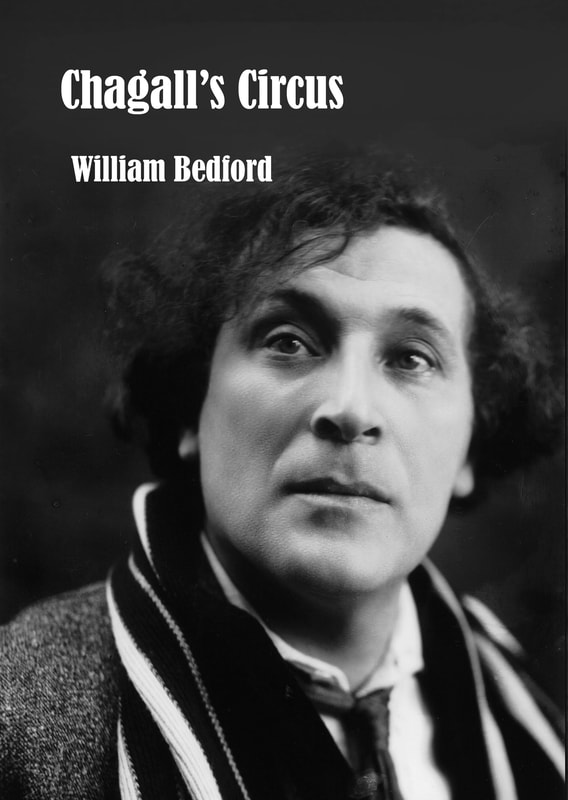

Chagall, in his long life, experienced some of the most dramatically troubled periods of history. Bedford writes of it boldly, slipping seamlessly into the painter’s voice. The poems are never simply descriptions of the paintings; but are set within history and biography.

In the opening poem, Self-Portrait with Brushes (1909), Bedford has extracted the painter’s shtetl childhood, incorporating images: the flowers, the cow, the fiddler, that run throughout Chagall’s art — All the poetry of life glows in sadness,

and his (father’s) silence is a forest of imagined flowers,

like the cow sleeping on the roof of our barn,

the fiddler leading the bride to her wedding.’

The second poem-painting, Grandfather’s House (1923) is of a child-like sketch of a house, with two windows. The voice is Chagall’s, a boy experiencing the vibrant world around him:

I spent my childhood devouring horizons,

seeing angels in the pattern of the carpet.

but warned ‘of the hunger hiding in colours, / the graveyards at the end of rainbows.’ Bedford unpicks the folkloric mythology Chagall created of his childhood in Vitebsk, his vibrant colours in marked contrast to the grey reality of poverty and fear experienced by Shtetl Jews.

The poem, Red Nude Sitting Up (1908), references Chagall’s romantic and sexual awakening:

my canvas was all nipples and angels

and despite the wild nights of St Petersburg

I painted my red nude sitting in Vitebsk.

All roads, inevitably, lead back over his shoulder to Vitebsk.

In the final lines, Bedford is the painter ‘covering the canvas in a horse blanket / to protect the villagers from their own fear,’ noting that his family ‘always preferred photographs.’ One recognises the stiff family portraits of that period.

In section 2, ‘The Paris Years’, the poet-painter takes on the art establishment labelling Chagall’s work against religion and poverty as ‘surreal.’

Yes, the man has the head of a bull,

and the girl wraps herself round his shoulder.

You can see that any night in Montmartre, (To my Betrothed, 1911)

In the following poem, I and the Village (1911), Bedford builds on its epigraph: ‘But perhaps my art is the art of a lunatic:’ He writes: ‘My clownish inner world was all I needed …

I have collected these fragments from my dreams

the paintbrush fingering clouds’ (ah, fingering clouds!)

concluding with: ‘The poet naming what the painter painted. (the poet here, Chagall’s-friend, Blaise Cendrars)

That was not what I meant at all

My art may be the art of a lunatic,

but Surrealism is only the name of an era.

I love the way the poet Cendrars acts as a counter-balance between the poet Bedford and the painter in critiquing the process between art and poetry and art. The effect is of a history of history within a history of art where politics, religion and love make up the Chagall circus:

But I had the Louvre inside me. The Fiddler

became The Praying Jew, the praying Jew

became The Smolensk Newspaper,

The Feast of Tabernacles became my feast. (The Fiddler (1912-1913)

The penultimate poem, Couple on a Red Background, references the painter’s second marriage to Valentina Brodsky. Bedford uses some lyrical description: ‘The man is tenderness, / his arm, the arm of nature’s protection,

The painter-poet voices join in unison, leaving us with ‘Stalin fiddling with his black moustaches, / Hitler saluting the gods in his mind.’

This collection is a banquet for the senses, which in other hands than Bedford’s, could be overwhelming. That it is not, begins with the poet’s skill in setting up a sound, containing layout. The narrative, no matter how intense and detailed in its content, tells the story of a life with grace and precision. Here is a book that that can be consumed with relish once and returned to with pleasure again and again.

U.S.-born Wendy Klein has published three collections: Cuba in the Blood (2009) and Anything in Turquoise (2013) from Cinnamon Press, and Mood Indigo (2016) from Oversteps Books. She is currently working on a selected and assorted pamphlets.

You can order your copy of William Bedford’s, Chagall’s Circus, (Dempsey & Windle) here: https://www.dempseyandwindle.com/william-bedford.html