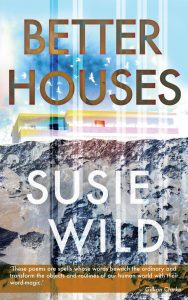

Susie Wild’s Better Houses announces a new, highly distinctive and exciting poetic voice. The subjects of this collection – a boyfriend mowing the lawn, an ill pet, a pub crawl – are universal, and give the poems an immediate accessibility. The author’s balance between opening the door for the reader, and then hitting them with the poem’s highly original approach to language and a slightly slant way of looking at the world, make these poems highly entertaining and rewarding.

One thing I was immediately struck by was the collection’s management of shorter poems. ‘The Elephant Fayre’ tells the story of someone deciding to run away at the age of six. The great title, and the poem’s opening, introduce the strong idea with admirable economy: ‘You were in a hurry to leave/home. The summer of ’85, and you were/six.’ From here, we move into a distinctive linguistic approach, which captures childhood perfectly: ‘you raced/flutterbies. Certain you belonged/at this festival of gadabouts…’ Most importantly, the poem has a great ending which really makes it stand up and live: after the runaway child has ‘found/a new family – a gypsy/caravan to call/your own,’ we have this marvellous last sentence: ‘They paid you/in ice cream, then – the traitors –/they gave you back.’

This great formula, of accessible ideas, distinctive language and a telling ending, enlivens a number of poems across the collection. ‘Thirst’ opens with a highly dramatic sentence:

My head is under

the surface,

my grandfather’s hand

holding it down for 1, 2, 3,

a punishment for something,

in the flooding shallows

of the stream.

From here we move into some lovely language – the sea ‘Spits me out grainy,/briny-eyed, starfish-limbed’ – before a jump forwards in time gives us this stunning ending: ‘Now I sleep beside a tumbler,/liquid lapping the brim.’

‘Delivery,’ similarly, begins with an everyday event, and these reflections on fertility:

When she collects,

spilling news

of her purchase –

a changing mat –

I realise she’s pregnant. Not

fat, our Kiwi at no. 23.

The opposite of what

people say about me, blooming

with my desk job diet.

The skilful shift in approach in the final sentence offers us a wonderfully evocative image, opening the poem out, and giving it a lingering power which has us coming back to it:

See the baby-grows

in rank: empty soldiers

on the washing line out back.

These exemplary shorter poems are complemented by the more sustained pieces in this artfully-sequenced collection. I was particularly taken by ‘Prep,’ a moving description of experiences at boarding school. Alongside a number of poems, including ‘The Lash Museum,’ the poem showcases the poet’s wonderfully clear eye for childhood memories. The emotive power of ‘Prep’ is maximised by its unusual focus. The poem’s first section concentrates on the trunk the speaker used to carry possessions back and forth to school, while the second section focuses on food. The poem is a sort of memoir-by-luggage-and-food then, and this unusual choice of focus really disciplines material which could be sentimental into something which is really powerful. The poem’s second section has some excellently-observed memories of childhood: ‘the thrill of Saturday movies in the boy’s halls, the gift/of changing the gears on the minibus drive/back.’ The first section is perhaps even stronger, giving that sense of lugging so much – clothes, relationships, anxiety – back and forth from home to school, which is so much a part of that experience. I loved this description of the trunk: ‘Wine-coloured, brass-tacked,/back then the trunk puff-chested a term’s worth of bedded/un-belonging.’ That verb ‘puff-chested,’ to describe the crammed trunk, but also the pride of the child heading off to school, is a delight.

‘The Art of War,’ a similarly sustained piece, draws on the famous Chinese military treatise to explore the realities of a contemporary relationship. The role of technology in love these days combines with the military vocabulary to strong effect: ‘I…wait for the artillery fire//of texts.’ The poem works through the anxieties of modern relationships – a borrowed laptop, speculation over engagement rings – towards this highly effective final sentence: ‘Deleting my browser history, I gather/the weapon of myself.’

Arguably even more intriguing are the two extracts we are given from a longer sequence, ‘Sex Change Disco.’ The first fragment is full of interesting and evocative lines: ‘a bashful Jack-the-lad smirk turns Jane,’ ‘I’m swan, laying belly to riverbed,/to wet stone, wriggling//in the hour between the dog and the wolf.’ The second extract opens with these descriptions and invitation:

All the creatures of the dark visit to take a look

at her. She is illuminated – a city species – in a glowing

glass box. See her dance. See her flap

about.

This fragment works towards another powerful and troubling ending:

They ask ‘boy or girl?’

We might have to dissect her to tell.

The notes at the back of the book tell us that these exciting fragments are part of a longer sequence, a collaboration with an artist, and one thing I wondered was whether a website link could be provided to allow the reader to see the whole sequence. In this sense, ‘Sex Change Disco’ is representative of Better Houses as a whole, as, like all the best collections, it leaves the reader wanting more. The marriage of clarity and accessibility with the highly distinctive voice which is evident in these poems, excitingly and genuinely all this author’s own, make this an accomplished and auspicious debut, and make this poet’s future work something to greatly look forward to.

Order your copy of Better Houses by Susie Wild here: https://www.parthianbooks.com/products/better-houses