‘Because of Him, Hummingbirds Will Die’

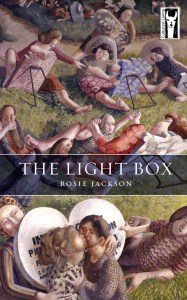

In a collection called ‘The Lightbox’ one might not be surprised that thirty five of the sixty nine poems within contain the word ‘light’, but the same number of poems also contain ‘love’, and there’s quite a bit of kissing going on as well. There’s also wonderfully rendered ekphrasis, with particular emphasis on the work of British artist Stanley Spencer to begin each of the six sections, and the collection ends on a high note with an angle on one of Spencer’s Resurrection paintings with ‘bodies that cannot have enough of each other,/ this love that is always being made.’ Be stabbed in the heart or lifted to great heights, and throw into the mix a whole stream of other characters: artists (Daguerre, Grainger McCoy, Masaccio, Barbara Hepworth, Georges de la Tour, Picasso, Joseph Wright) historical (Mary Shelley, Lazarus, Leonard Woolf, Flaubert, John Donne, Margery Kempe, Mrs Thatcher) and mythical (Penelope, Persephone, Demeter, Orpheus and Eurydice), then add heaped spoonfuls of imaginative sensual play, a little death, pain, tenderness, the trials of relationships, and Rosie Jackson brings together the ingredients for a quite remarkable collection.

The landscapes in which she sets her characters in order to consider aspects of their lives, or life itself, are beautifully realised. Where these characters are artists, she sometimes employs their work to explore more personal issues. ‘In Which I Liken Our Ending to Masaccio’s Expulsion’, for example, the restored painting of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden has the fig leaves removed. They’d been painted on three centuries after Masaccio for the sake of decency. The resulting poem offers more about her relationship, as the title suggests, than the inviting opening line that speaks directly of Eve as she is once again portrayed without the cover-up leaves.

Similarly, in the poem ‘My Uncle Visits Mount Vesuvius, 1944’, we are delivered into a painting. Joseph Wright undertook a series of thirty or more of Mount Vesuvius in eruption, and the poem draws from both the image of humbling forces of nature in the artwork, and the family grief of an uncle killed thereabouts, presumably in the war. ‘I don’t know who carried his body -/ there were no fathers or brothers left.’ And what a powerful ending to a poem like this. Speaking of her mother (mum), ‘She kept his spectacles on the sideboard for years.’

Some images are dealt with more directly, but they speak to the emotions powerfully. She writes of Daguerre, who in 1839 claimed, ‘I’ve seized the light’ in reference perhaps to his Daguerrotype photograph ‘Boulevard du Temple’ which includes the earliest known candid photograph of a person. The poem makes the hairs on the neck spring to attention with lines such as ‘a bootblack, head bowed,/ the first ghost to be caught on camera,/ condemned to be in service forever.’

Then there’s Picasso, or rather Picasso’s reflection in the window of the Café de Flore. There’s something quite haunting, but at the same time mesmerising about the notion of him seeing his own reflection remain standing in the café window when he sits down. He ‘tries not to glance round/ and see the self in the glass/ hanging there/ like a detached retina.’

Other characters are placed in unlikely settings or considered in suprising ways: Mrs Thatcher leaves her body and meets St Francis, Demeter takes up embroidery and Persephone blames the dress, but these are effective routes to exploring and keenly observing. We see Mrs Thatcher, her mind uncoupled, rising up from her sceptered isle, becoming unsettled, ‘till the light feels more like darkness,/ coal dust,’. So much depends (not on a red wheelbarrow), but on the richness and the weaving of Rosie Jackson’s own myths and inventions.

And returning to love and light and pain, they are ever present to a greater or lesser degree, whether those words can be found in the poems or not. Sometimes they are like a sharp injection into the senses. The eye for small detail lifts these poems from those we have heard before: ‘stepping round petrol puddles’ in a wedding dress that she can’t remember, ‘when you climbed into bed with wet hair’ in ‘Had We Known’ and in ‘Seated Nude’ (another of Stanley Spencer’s paintings), we hear his ex-wife, Hilda’s ‘anger squashed like pressed flowers.’

Stanley Spencer said he wanted to put himself in his work, and as an obvious enthusiast for this twentieth century artist’s life and paintings, Rosie Jackson likewise puts herself into her poems. They are deft, have a strong voice, and if reading extraordinarily good poems full of light, love and quite a bit of kissing, appeals, then ‘The Light Box’ comes highly recommended.

The Lightbox by Rosie Jackson is published by Cultured Llama, and is available here: http://www.culturedllama.co.uk/books/the-light-box